Does COVID-19 pose a risk for rural areas?

COVID-19 poses a risk for all people.

The majority of the initial cases of COVID-19 were registered in urban areas. In many countries, initial cases were high in urban areas due to the arrival of international travellers. Early-stage transmission of COVID-19 tended to also occur in confined and densely populated urban areas.

As the pandemic progressed, we noticed an increase in the number of COVID-19 cases occurring in rural areas. The spread of cases from urban to rural areas can occur quite rapidly, particularly as lockdown conditions are imposed or lifted. For example, in India, the lockdown measures resulted in many people in urban areas suddenly returning to their home villages for a variety of socio-economic reasons, such as loss of employment opportunities, closure of schools and universities, and to provide social support for their families. A second wave of migration from Indian cities to rural areas also occurred as lockdown restrictions were lifted. Travel between urban and rural areas on crowded transport can also increase the risk of exposure.

What might increase vulnerability to COVID-19 in rural populations?

Below we highlight some factors which may affect the management of COVID-19 in rural areas:

Reduced health care access – People in rural areas may have to travel further to access healthcare and are less likely to have access to acute hospital care or specialised health care staff. The lack of access to healthcare may result in those people who are ill with COVID-19 being cared for at home. Healthcare facilities in rural areas are also more likely to lack access to adequate personal protective equipment (PPE) and water (as of 2021, 1 in 3 health facilities lack access to water and soap) which would make it difficult for health workers to practice proper and frequent handwashing, as recommended to maintain effective infection prevention control (IPC) and curb the spread of the virus. In health care settings where water is scarce, the increasing demand for water may result in water being reused, which can increase the cross-transmission of COVID-19 and other hospital-associated infections.

Access to COVID-19 testing – Limited access to health care may compound limited access to COVID-19 testing. In high-income countries, rural areas struggled to expand COVID-19 testing at the necessary scale and speed. This has been more pronounced in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), where rural areas already have limited access to health services and where remote regions are harder to reach. This means that initial cases in rural areas go undetected, leading to further transmission and causing the overall burden of COVID-19 in rural areas to be underestimated. This situation has made detecting and managing COVID-19 cases in rural areas more challenging. In many countries, there have been efforts to improve testing capacity and processing times. This has included decentralisation of testing facilities and pool testing of multiple samples.

Older populations – There are many factors that increase the risk of severe health consequences from COVID-19 (discussion of these are addressed elsewhere). One difference between urban and rural areas relates to demographics, as rural areas typically have a higher proportion of older people than urban areas. This is because younger populations often move to urban areas to seek education and employment. We know that COVID-19 is more likely to have severe health consequences on older people, as many are likely to have other health co-morbidities, and so proportionally, rural areas face a more severe strain on their health systems and may see higher mortality rates. However, LMICs typically have younger populations overall, which may result in COVID-19 outbreaks causing less mortality than in high-income settings. For more information on supporting older people and people with disabilities, see this Hygiene Hub resource.

Modes of socialising and communicating – In rural areas, large gatherings such as religious events, funeral events, celebrations, market days, or gatherings at workplaces and schools are still key parts of community life and may be more common than other forms of social connection and communication (e.g. the use of mobile phones to communicate). During outbreaks, this may facilitate transmission in ways that are different to transmission patterns in urban areas. In many countries, governments have imposed restrictions on gatherings during outbreaks, but these may be harder to enforce in rural areas.

Vulnerability to secondary impacts – Rural populations might be more vulnerable to exclusion and discrimination due to existing inequalities between urban and rural regions, exacerbating the secondary impacts of COVID-19. For example, people in rural areas are typically less wealthy than in urban areas and people in rural areas are more likely to be employed within the informal sector, or as seasonal agricultural workers. The combination of these factors means that families in rural areas may be disproportionately affected by the economic impacts of COVID-19. For example, families may face food security challenges, due to direct loss of income or a reduction in remittances coming from family members in other regions. Rural areas may have a higher risk of food shortages, due to travel restrictions and the impact of COVID-19 on supply chains. Rural areas may also experience shortages in the supplies of other key items such as soap, sanitizer, masks, chlorine and gloves.

What are the challenges of COVID-19 prevention programmes in rural areas?

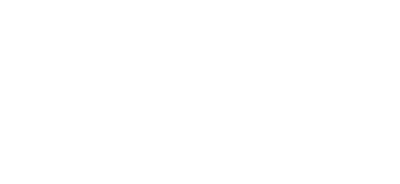

Access to handwashing facilities with soap and water - In rural areas, there is often a lack of access to adequate handwashing facilities at home and in healthcare facilities, schools, workplaces and in public areas. An estimated 45% of the rural population globally don’t have access to a basic handwashing facility with soap and water at home; this disparity further increases to 81% in low-income countries (LMICs). The figure below shows the disparity in the availability of handwashing facilities between rural and urban contexts in several countries.

Source: Jiwani SS and Antiporta DA2020)

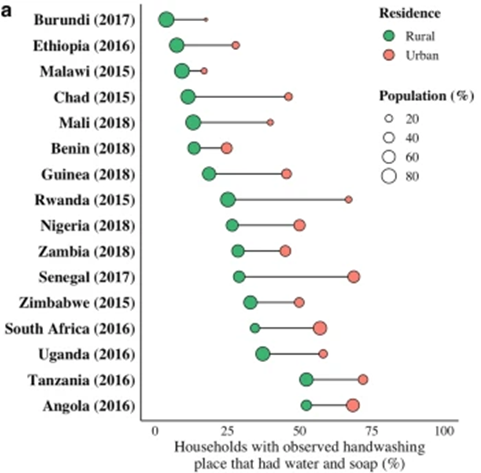

Urban populations are also much more likely than rural populations to have soap available within the household as shown in the figure below. The reduced availability of both soap and handwashing facilities requires that response initiatives invest heavily in products and infrastructure in order to enable good practice.

Source; Kumaret al 2017)

Reliable water access - This is essential to ensure adequate handwashing and cleaning. In rural areas, access to basic water supplies is lower than in urban areas, with 81% of the population having access to basic water supplies in rural areas, compared to 97% in urban areas. Only 60% of people living in rural areas have access to a water supply on their premises (compared to 88% in urban areas). Water is also less available when needed in rural areas (only 68% of people living in rural areas have water available when needed compared to 86% in urban areas). Water availability in rural areas can be further limited by unreliable supplies from poor water point functionality and variable water quantity. Unreliable water supplies can increase the risk of transmission, by reducing water available for handwashing, and increase the time spent queuing for water. Water availability is likely to vary over time, being more restricted in a long dry season or after extreme weather events. These extreme events continue to happen during COVID-19 and often affect rural populations severely. For example, in Bangladesh, after cyclone Amphan in May 2020, water supplies were damaged restricting access to safe water further. Flooding in the same region in July 2020 also reduced access to safe water. We also know that unreliable water supplies have created challenges during other outbreaks. For example, in a cholera-prone region of DR Congo, the inconsistent availability of water led to increased cholera transmission. It is possible that movement restrictions may have more severe impacts on the ability of rural populations to collect water from communal water points. Moreover, water access can also be a potential source of transmission if physical distancing is not practised at communal water points.

Reduced literacy level - People in rural areas may have reduced access to formal education and as a consequence, may have lower rates of literacy. This means that printed materials or messaging about COVID-19 will be less suitable for these audiences.

Reduced access to communication channels - People living in rural areas have historically been less able to access mass media like television and radio. This has been due to blackspots within broadcasting coverage, economic factors, and access to technologies. However, there are indications that this is changing throughout Africa and Asia and more people are gaining access. Radio, in particular, is now more able to reach people in rural areas of Sub-Saharan Africa. Similarly, people in rural areas are less likely to have access to mobile phones and the internet and this can further restrict communication with populations at this time. Given these challenges, one of the most common ways of engaging rural populations in public health promotion activities has been to organise community meetings or gatherings. However, this presents a risk of increasing COVID-19 transmission. For further information on communication channels, see our resource.

Perception of risk - Given that COVID-19 cases typically originate in urban areas and that, as a consequence, news headlines and response activities typically focus on the COVID-19 situations in urban areas, it is possible that rural populations may consider that they are not at risk from COVID-19. In rural areas it may be useful to identify opportunities to share the stories and experiences of COVID-19 cases living in these areas, so that rural populations realise that they too are at risk.

What should be done as part of COVID-19 response in rural areas?

This section provides practical actions to be undertaken in rural areas during the COVID-19 pandemic, while also considering longer-term actions to promote sustainability. These focus on key COVID-19 preventative behaviours and the infrastructure and products that support them.

1) Promoting and supporting hygiene practices

● Handwashing infrastructure - Programmes should focus on scaling up handwashing facilities in households and public settings such as schools, workplaces, religious sites and markets. A barrier in rural settings can be access to the supplies needed to construct a facility and the cost of constructing such facilities. In some rural settings, this has been resolved by promoting handwashing facilities that can be made from locally available materials, like the Tippy-Tap design in this video.

However, experiences of promoting these kinds of innovations in prior outbreaks or as part of short-term hygiene promotion programmes have shown that often facilities made from local, low-cost materials may not be very sustainable solutions and need to be accompanied by ongoing operation and maintenance mechanisms. Therefore, in public settings such as in schools and health care settings, it may be cost-effective to build handwashing facilities that are more durable. WaterAid has developed this guide for building public handwashing facilities. This document builds on other research which shows that handwashing facilities should be designed in partnership with local communities, be easy to use and should be attractive so that handwashing becomes desirable to practice. For more information on handwashing infrastructure, see this Hygiene Hub resource.

● Soap availability - In rural areas soap is often not kept at the handwashing facility. This is often because soap is a valued item and people do not want it to be wasted or stolen. Handwashing can be enabled in these settings by encouraging people to keep soap in nets or to attach soap on a rope, so that it cannot be easily removed from the handwashing facility. Soapy water, made from dissolving laundry powder in water, is another cost-effective and acceptable way of keeping soap at the handwashing facility. If soap supplies are a major challenge in your area, it might be worth considering supporting local residents to make soap or alcohol-based hand rub (ABHR). Read this guide for more information on how to do this and whether it is likely to be appropriate in your context. While ABHR has typically been less common in rural areas, increasing its availability may be useful to overcome barriers of being able to clean hands when outside the home, or while undertaking farming work. It may also be appropriate to promote alternative handwashing products in some settings.

● Creative hygiene promotion - Hygiene promotion should always be done alongside investment in hygiene infrastructure and products. Conducting hygiene promotion in areas where facilities are lacking, may be ineffective. In this resource, we suggest some simple handwashing promotion activities which could work across a range of settings. In rural areas, it may be more challenging to reach populations. This requires programme implementers to take time to assess which delivery channels are likely to be most effective, acceptable and safe to conduct. For more on how to do this, read this resource. In rural areas, you may be more able to build upon existing communication structures (as communities may be more close-knit than in urban areas) and communication mediums, such as radio or physically distanced house-to-house visits, could be considered.

2) Ensure water is affordable and accessible

● Affordability - Many rural communities have been disproportionately affected by the economic impacts of COVID-19, due to higher unemployment and reduced remittances. Ensuring that water remains affordable is essential, so that hygiene can be maintained to prevent the transmission of COVID-19 and to reduce other health impacts. Some countries have waived water bills or provided water subsidies during the pandemic. Other countries have swapped to enable digital water payments so that human interactions can be minimised whilst supporting financial planning and subsidies. However, these approaches usually only benefit those with access to piped water (likely to be a lower proportion of the population in rural areas). In rural areas, the COVID-19 response should prioritise reducing payments for essential water services. Managing affordability also requires consideration of financial sustainability, as reduction in revenue, such as has been seen in some countries, may affect the ability of smaller water service providers to afford ongoing treatment and maintenance.

● Access - The distance and time to collect water can affect how much water is used by a household. During the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, some governments focused on building new water infrastructure to reach underserved regions; scaling up maintenance efforts to fix existing but damaged water facilities; and working with the private sector to fill key gaps in the short-term water supply. Accessibility to parts and materials has been reported as an issue in some rural areas, limiting the ability to repair damaged water points. In rural areas, the COVID-19 response should prioritise the maintenance of existing but damaged water points, and consider availability of materials. In the longer-term, it should also include building more water points (particularly in areas where people currently travel more than 30 minutes to collect water) and providing increased training on how to construct and maintain these.

3) Reducing risk of transmission in public spaces

Any setting where people congregate creates risks for COVID-19 transmission during outbreaks. However, it may still be necessary for people to visit certain locations such as markets, distribution centres, and healthcare facilities, in order to have access to food, water, household essentials, healthcare or to maintain an income for their family. In rural areas, this means that people may still need to travel on public transport to support their families and participate in economic activities. Measures to support essential movement while managing transmission risks include:

Promotion of fabric face masks: Many countries are promoting the use of face masks in public settings where physical distancing can be hard to maintain. For a deeper understanding of the guidelines and evidence around safe mask use, see the WHO’s IPC guidelines, updated in January 2023. During outbreaks in rural areas, initial efforts should focus on increasing the availability of affordable face masks. This could include initiatives to encourage local community groups to make and sell fabric face mass.

Local solutions to encourage physical distancing: There are a range of low-cost measures that can be introduced to encourage physical distancing in rural environments. These include physical markers and environmental nudges (simple cues to influence behaviour) at public places. Hand hygiene stations or hand-sanitiser dispensers should also be made available at these locations, with clear processes set out for whose responsibility it is to maintain the facility and refill soap and water or sanitiser. Below we provide some examples of physical distancing measures in rural settings:

● IOM Ethiopia stuck painted sticks in the ground, to mark out physical distancing measures (as shown in the photo below) and constructed handwashing facilities at water points to reduce the risk of transmission at rural water points.

Source: IOM Ethiopia

● In Kenya, the image below was posted at rural water points to help people understand how far they should stand apart.

Source REACH

● To encourage hand hygiene practice among Filipino students, schools adopted environmental nudges, such as footprints painted on the ground leading to handwashing stations, arrow stickers pointing towards the soap dish, and “watching eyes” above the sinks.

Source: IDinsight/Nhu Le

In Myanmar, several regional municipalities adapted their local markets to facilitate physical distancing. In some cases, this required moving the markets to larger spaces, imposing restrictions that sellers had to be from the local area and adding demarcations on the ground, to ensure vendors and consumers could remain at a distance.

An adapted market space in a small town in Myanmar. Source: The Irrawaddy

Safe distribution of goods - As the economic impact of COVID-19 takes its toll on rural populations, many local governments or response organisations may consider distributions of essential items in rural areas. These need to be managed carefully, so that distributions do not unintentionally become sites of potential transmission. For ideas on how these can be done safely, see this resource.

Working with larger employers in rural areas - 75% of the world’s poorest people work in agriculture and this represents a large portion of rural populations in LMICs. Seasonal agricultural workers may disproportionately impacted by COVID-19. Taking preventative measures to reduce COVID-19 transmission will necessitate collaborations with agricultural employers or other large employers within rural areas. General guidance on measures that workplaces can take to reduce transmission and risk for employees have been produced by the WHO and Occupational Safety and Health Administration. For agricultural work, specific adaptations may include the provision of face masks, the provision of additional handwashing or sanitising stations, regular disinfection of equipment, and adapting shifts, accommodation and transportation, so that they comprise the same group of workers each time to minimize the number of interactions any one staff member has.

Encourage community support systems

In rural areas, communities are often closely-knit and it is more likely that people will have strong social groups and established support systems to address local challenges and needs. There are opportunities to build upon and work with these existing systems, to enable an effective response to COVID-19 and contribute to longer-term resilience. Work with communities to identify individuals or families who might be disproportionately impacted by COVID-19. This could include individuals who are prone to more serious forms of the disease, such as older people link or people with pre-existing conditions, as well as families who are likely to be disproportionately affected by the secondary impacts of COVID-19. Discuss with leaders within the community about how the community can best support these families. For example, in many counties, older people and people with pre-existing conditions are being asked to ‘shield’ themselves to reduce their chance of getting COVID-19. In such circumstances, we have seen volunteer networks develop and play a role in delivering water, food and medication so that these individuals can maintain physical distancing.

Connect your programme with other services

As mentioned above, people in rural areas are likely to experience a range of secondary impacts of COVID-19 and many people in rural settings may already be dealing with a range of other challenges. Prior to and during the implementation of your COVID-19 response program, make sure to engage with communities and understand their needs, challenges and local solutions. Where possible, try to link your actions with other community services (such as primary health care, nutrition programmes, maternal and child health services) being provided by governments, civil society groups and non-government organisations, to ensure that together you are addressing all local needs.

Does COVID-19 create opportunities for improving the resilience of rural communities?

COVID-19 offers the opportunity to build resilience in rural areas against future outbreaks and reduce the enduring burden of diarrhoeal diseases, respiratory infections and Neglected Tropical Diseases. The public messaging and prioritisation of handwashing and hygiene practices during the pandemic highlighted that more needs to be done to meet the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) related to water, sanitation and hygiene (Goal 6). The pandemic has led the WHO and UNICEF to create the Hand Hygiene For All initiative, which sets out a plan for how we should respond to COVID-19, rebuild and reimagine the state of hygiene globally. Within this, it is acknowledged that changing the state of hygiene and building resilience against disease, requires a coordinated and strategic approach combining:

Advocacy actions to influence national policy

Large-scale local-level action to create normative change

Financial and infrastructural investment to create an enabling environment

Research, learning and monitoring of programmes to improve the quality of implementation.

The Hand Hygiene for All initiative also highlights that action needs to happen within a range of settings including:

Health care facilities

Schools and day-care centres

Workplaces and commercial buildings

Refugee, migrant and other camp-like settings

Prisons and jails

Markets and food establishments

Transport hubs, places of worship and other public spaces

Long-term care facilities

At home

This larger framework is particularly relevant for thinking about resilience building in rural areas, because these regions have historically been harder to reach with WASH services, infrastructure and programmes. For example, we now have the opportunity to advocate for funding to support creative and sustained handwashing behaviour change work at a national level. The renewed emphasis on comprehensive IPC practice at health facilities, has created an opportunity for rural health service stakeholders to advocate for dedicated funding to operationalise and maintain WASH infrastructures to sustainably support recommended IPC and hygiene activities for both staff and users of rural healthcare facilities. The COVID-19 pandemic may create opportunities to improve rural water services, through fixing broken infrastructure, constructing new water points, and providing increased training for maintenance and construction.

Editor's Note

Authors: Katrina Charles, Li Ann Ong and Robert Hope

Review: Balwant Godara, Peter Winch, Kondwani Chidzwizisano, Boluwatito Awe

Last update: 03.06.2023