What is the difference between monitoring and evaluation?

This resource covers monitoring and evaluation (M&E) principles and practical ways of applying these to hygiene during infectious disease responses. We also provide some general principles for how to understand whether your project is having an impact on relevant preventative behaviours.

M&E allows for the assessment of the performance of a project. M&E should be thought of as a single process, utilizing data collected on an ongoing basis and at different time points. M&E data supports learning and accountability for all stakeholders, including funders, beneficiaries, implementers, and policy makers.

Monitoring is a continuous process of collecting data throughout the lifecycle of a project. It involves the collection, analysis, communication, and use of information about the project’s progress. Monitoring systems and procedures should provide the mechanisms for the right information to be provided to the right people at the right time, to help them make informed decisions about project progress. Monitoring data should highlight the strengths and weaknesses in project implementation and enable problems to be solved, performance to improve, success to be built on and projects to adapt to changing circumstances. Often routine monitoring data feeds into process evaluations as described below.

Evaluation refers to the systematic assessment of whether a project is achieving its stated goals and objectives as determined at the design stage and/or the extent to which the program has resulted in the anticipated outcomes and impact among the target population and if any unanticipated outcomes or impact have resulted. Please see this resource for detailed definitions of each of these. Evaluations often take place at baseline, midterm and endline. Evaluation can be distinguished from monitoring and regular review by the following characteristics:

Scope: Evaluations are typically designed to answer focused questions on whether the project outcomes and impacts were achieved, how these impacts were achieved, if the proper objectives and strategies were chosen, and whether the intervention was delivered as designed.

Timing: Evaluations are less frequent and most commonly take place at specific times during the project cycle.

Staff involved: Evaluations are often undertaken by external or independent personnel to provide greater objectivity. This is because if project staff conduct the evaluation, results may be biased.

Users of the results: Evaluations may be used by planners and policy makers concerned with strategic policy and programming issues, rather than just managers responsible for implementing projects.

What is a ‘theory of change’ and how does it inform program monitoring and evaluation?

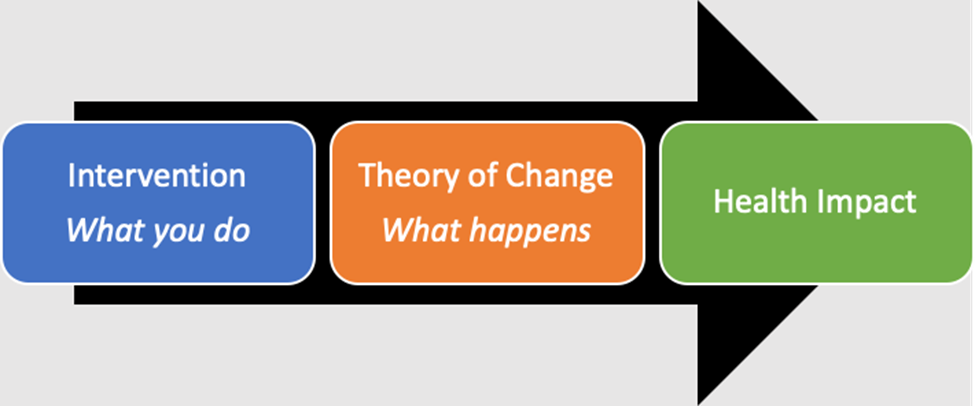

One of the most useful tools for developing an M&E plan is to develop a theory for how your project is likely to be able to achieve its outputs and the associated outcomes and impacts. This is what is often called a ‘theory of change’. Developing a theory of change will allow you to establish appropriate M&E processes.

What is a theory of change?

A theory of change describes how your project proposes to bring about a change in behavior or health outcomes by outlining a step-by-step series of causal events. When developing a theory of change, it is useful to use a ‘backwards mapping’ approach, which starts with the desired outcome and then works backwards, identifying the short- and medium-term actions and objectives required to achieve this. A theory of change is based on assumptions about what needs to take place and incorporates an understanding of how the context might support or hinder the success of the intervention.

Source: Matthew Freeman

There are many different terms used to describe the various components of a theory of change. Organizations may use different structures to understand the causal nature of a theory of change, including logframes and impact pathways.

We use the following terms and definitions in this resource:

Inputs: The raw materials required (e.g. money, materials, technical expertise, training, relationships and personnel) by your project in order to deliver activities and achieve the outputs and objectives

Activities: The process or actions taken that will transform inputs and resources into the desired outputs.

Outputs: The direct results of the project activities. All outputs are things that can be achieved during the period of the grant and are linked to the objectives and goals.

Outcomes: Specific statements of the benefits that a project or intervention is designed to deliver. These should support the goal and be measurable, time-bound, and project-specific. Many projects have more than one objective.

Impact: The long-term, large-scale challenge that your program will contribute to addressing.

Source: Matthew Freeman

The utilisation of inputs and the delivery of project activities leads to a cascade of events where outputs result in behavioural outcomes and health impacts. If we do not see the change we expected from a project, then we have either ‘theory failure’ (our theory of change was wrong) or ‘implementation failure’ (we did not deliver the project correctly). Process evaluation helps determine if there is implementation failure. M&E along the theory of change can help determine if there is theory failure.

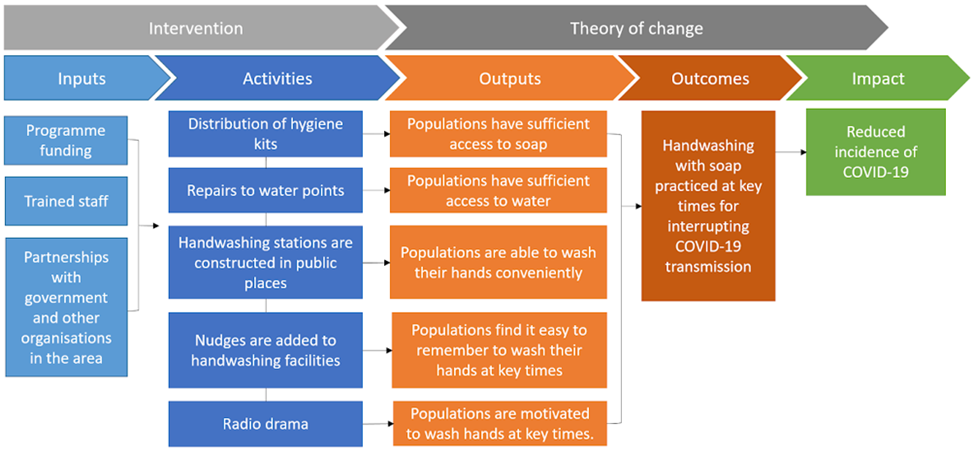

A worked example of theory of change applied to a handwashing behaviour change project for COVID-19

Here we include an example of a simplified theory of change for handwashing with soap for the control of COVID-19, though the example could be applied to other infectious diseases with similar modes of transmission. The actual theory of change for any individual project may be more specific and should include indicators that are more measurable.

Source: Matthew Freeman

Monitoring and Evaluation and the Theory of Change

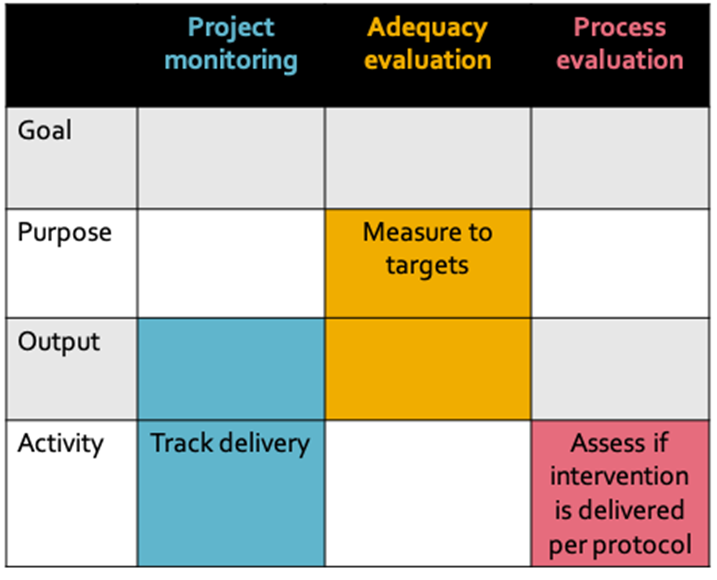

A well-articulated theory of change can be used to inform M&E activities. Monitoring is an ongoing process and should primarily focus on indicators related to activities and outputs. It may also include routine assessment of project outcomes. Evaluation focuses primarily on the later stages of the theory of change, assessing the achievement of outcomes and impacts. The components covered by evaluations will depend on the type of evaluation being done.

There are several types of evaluations that could be used in the development, delivery, and assessment of public health interventions. These are defined below:

Process evaluation: These document how a project is implemented and what was actually delivered compared to pre-defined plans. Process evaluations often assess the following:

Fidelity and quality – Extent to which a project was implemented as planned (e.g., did all of the steps outlined in the initial proposal or project manual take place).

Completeness - This refers to the number of project activities delivered as planned. For hygiene projects, this could include the number of hygiene kits distributed, the number of households visited, or the number of radio adverts aired. This is also sometimes called the ‘dose delivered’.

Exposure - This describes the extent and frequency with which the target population actively engages with the project activities. For hygiene projects, this could include the use and continued use of hygiene kits, attendance at training sessions or household visits, and the number of people hearing media messages. This is also sometimes called ‘dose received’. Exposure is different to completeness, because it focuses on real engagement. For example, for completeness, you may document that radio messages have been broadcast 50 times but when assessing exposure, you may find that your target population didn’t hear these messages, as the radio station chosen was not widely listened to.

Acceptability and satisfaction - This describes the extent to which participants and community members felt that the project addressed issues relevant to them and was delivered in a manner that was acceptable and appropriate for them.

Inclusiveness - This refers to the extent to which your project reached all of the people it intended to reach, including groups who may be vulnerable to discrimination and exclusion and or people considered as clinically vulnerable. For more information about making projects inclusive, see these resources.

More detailed definitions and information about each of these process evaluation terms can be found here. On this website you will also find a range of other resources on process evaluations.

Adequacy evaluation: These evaluations measure the extent to which a program or project has met predefined targets among the intended population.

These targets could be behavioral (for example: percent of the population practicing handwashing at key times), access targets, or health targets.

In an adequacy evaluation, success is measured against predefined targets which are set out at the start of project activities. Because adequacy evaluations do not compare projects against a control group, an adequacy evaluation cannot determine what would have happened if the project had not taken place (an important part of determining causation). As such, adequacy evaluations do not directly indicate if the project caused the measured changes in the intended population. However, if an adequacy evaluation measures indicators directly related to project activities and outputs and there are no other projects that are ongoing in that area, we can conclude that the changes are likely a result of the project.

Impact evaluation: The “gold standard” in public health, impact evaluations (which include randomized trials or quasi-experimental studies) determine if an intervention, project or program statistically impacted a key indicator of interest (e.g. health). This will often include the measurement of medium to longer-term outcomes and will examine cause and effect to understand if changes in behaviour or health can be attributed to your intervention. Impact evaluations require a control group, a set of units (e.g., households, communities, schools) that did not receive the intervention. These types of evaluations can be expensive and complicated. The use of impact evaluations may not be feasible or advisable in certain contexts.

For more information on adequacy and impact evaluations (plausibility and probability), we recommend reading this article which clearly explains not only what to measure for this type of evaluation, but also what can be claimed or demonstrated through each type of evaluation.

Source: Matthew Freeman

Which types of evaluations work best for hygiene projects?

In the context of outbreaks, the dominant approaches for M&E typically include monitoring and process or adequacy evaluations. During outbreaks, it is less common for impact evaluations to be used. This is because impact evaluations are typically more costly (involving external staff and tighter controls on how data is collected), introduce ethical challenges (such as the use of control groups), and require a behavioural or health outcome measure (likely to be challenging to collect with quality during outbreaks). For more information on why health measures are not widely used during outbreaks, see this resource. Instead, we recommend that project implementers prioritise assessing the progress of interventions against predetermined behavioural and access targets related to the project’s outcomes.

Given the scale of some outbreaks, there may be many organisations in your area collecting M&E data. To avoid duplication and data collection fatigue among your populations, try to coordinate your M&E processes with other organisations working in the same area.

Should we be tracking cases and mortality rates to understand whether our programmes are having an impact? - example of COVID-19

Note that whilst this section uses COVID-19 as an example, principles can be applied to other similar diseases. Tracking the incidence of COVID-19 cases and mortality is not recommended as part of programmatic impact evaluations. The reasons for this are described below.

Limitations of data on COVID-19 cases and mortality:

COVID-19 cases

COVID-19 cases can be either suspected, probable or confirmed through a laboratory test. Most of the national or global numbers of COVID-19 cases are of confirmed cases. However, the extent of testing varies across countries (e.g. 0.1 tests per thousand people in Indonesia to more than 100 tests per thousand people in Iceland), and data on testing is sometimes unavailable or incomplete. Aside from differences in testing strategies and protocols, there are other factors that might influence counts of cases including detection, definitions, reporting and lag times and these factors also differ across countries. In many countries, testing is limited to those who present with symptoms, however evidence suggests that people can be asymptomatic carriers and can transmit COVID-19.

COVID-19 Mortality rate

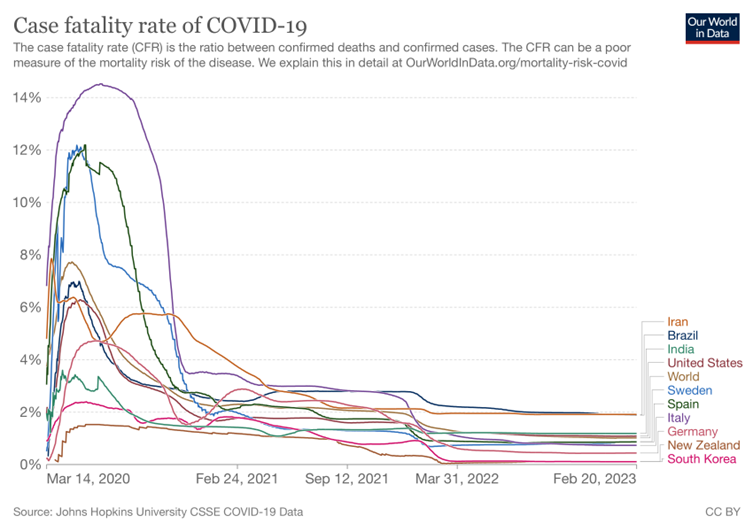

There are a number of different mortality frequency measures. When it comes to COVID-19, we often refer to case fatality rates, this is defined as the proportion of persons with a particular condition (cases) who die from that condition. In order to measure case fatality rate, it is necessary to know the total number of COVID-19 cases and the number of deaths due to COVID-19 among those cases.

During disease outbreaks, diagnostic testing is often not done systematically, which leads to us not having a good understanding of the total number of people, like we experienced with COVID-19. As testing is not done in the same way across countries, it makes it difficult to compare fatality rates in different populations regionally and globally. In addition to issues with defining the number of cases, there are also differences with how deaths involving COVID-19 are defined and issues of hidden deaths (people dying from COVID-19 who are never tested). Frequently this is a challenge during cholera and Ebola outbreaks, where there is both health facility AND community cases and deaths, making it difficult to understand the actual total number of cases and deaths. As a result, caution needs to be taken when interpreting the numbers of cases and case fatality rates during disease outbreaks, especially when trying to compare them across countries.

Given the unprecedented duration and severity of the pandemic, capacity in diagnostics, surveillance and reporting, treatment measures and uptake of preventative measures improved. In March 14 2020, the CFR varied from 0.22% in Germany to 6.81% in Italy and 3.74% globally. Meanwhile a year later after the first confirmed case of COVID-19, the CFR varied from 2.86% in Germany to 3.17% in Italy to 2.29% globally. Three years later since the pandemic started, we still have CFR’s of 1.19%, 1.89% and 1.91% being reported in India, Brazil and Iran respectively.

Source: Our World in Data

When designing measures to understand the health impact of your programme a common challenge is attributing any changes in incidence of cases and mortality to any specific program. This is difficult because:

In areas experiencing COVID-19 outbreaks, there are multiple actions being taken. These include actions by governments, businesses, non-government organisations and individuals or communities. It is likely that any changes in the epidemiological trend will occur as a consequence of the combination of these actions.

Community level preventative actions will not have a direct effect on COVID-19 death rates. Death rates are more closely linked to the capacity of healthcare facilities to manage severe cases and the proportion of the population who experience heightened vulnerability (e.g. due to existing medical conditions, age, or being vulnerable to exclusion and discrimination).

It is therefore advisable to measure programmatic impact across a theory of change to see whether the program achieved intended consequences along the pathway that could lead to a reduction in COVID-19 transmission, cases and resulting deaths. It is also important that expectations about what a programme evaluation will and will not achieve are managed from the outset so no one is expecting health impact data and understands why this isn't useful.

What if monitoring and evaluation processes show that my organisation's project didn’t work as expected?

Sometimes the results of M&E processes may be disappointing or not as positive as your organisation expected. It is often tempting to not share these findings with others in the same way that you may share positive findings. However, within the WASH sector there is renewed interest in learning constructively from failures. The Nakuru Accord encourages WASH practitioners to:

Promote a culture of sharing and learning that allows people to talk openly when things go wrong.

Be fiercely transparent and hold myself accountable for my thinking, communication, and action.

Build flexibility into funding requests to allow for adaptation.

Design long-term M&E that allows sustainability to be assessed.

Design in sustainability by considering the whole life cycle.

Actively seek feedback from all stakeholders, particularly end-users.

Recognise that things go wrong, and willingly share these experiences, including information about contributing factors and possible solutions, in a productive way.

Critically examine available evidence, recognising that not all evidence is created equal.

Write and speak in plain language, especially when discussing what has gone wrong.

During outbreaks, organisations may be even less likely to discuss and report programmatic failures - big or small - because they perceive the risks to be higher. However, effective sharing of challenges and failures can mean that these mistakes do not get repeated by others and that the whole sector benefits and is able to improve the outbreak response.

What other resources are there on Monitoring and Evaluation?

General M&E Resources:

The Intrac M&E Universe - A set of online learning resources covering a range of M&E topics. Includes useful guides on how to develop logical frameworks and theories of change. Some resources are available in multiple languages.

LSHTM resource list- a list of useful resources on process evaluations.

Accountability and Quality Assurance Systems – via the Global WASH Cluster, the AQAS provides a modular analytical framework that communicates guidance on monitoring approaches, standards and indicators for quality monitoring in key WASH areas.

ALNAP resources - A set of resources on how to improve M&E within humanitarian response.

Wash’Em M&E guide - A short brief with advice on how to do M&E during outbreaks and humanitarian crises.

M&E Templates - Tools4Dev provides several templates for assessments throughout the project cycle including an M&E plan template and an M&E Framework template.

Quality programme standards – WaterAid brings together standards and accepted ‘good practice’ in the wider WASH sector. Meanwhile their guide to support planning, monitoring, evaluation, and learning provides a structured approach to adaptive programming.

Compendium of Hygiene Promotion in Emergencies - a comprehensive guide from the German WASH Network, IFRC, the Global WASH Cluster and Sustainable Sanitation Alliance, published in 2022. Includes a chapter on Monitoring, Evaluation, Accountability and Learning (MEAL).

SAVE guidance on monitoring in insecure environments - Describes challenges and mitigation options for lots of remote data collection tools.

M&E online training course:

Disaster Ready - a range of courses on all aspects of monitoring, evaluation learning and accountability.

Global Health Learning Centre - M&E Fundamentals

Poverty Action Lab- a range of courses on impact evaluations, surveys and evaluating social projects.

Save the Children - an open course on all aspects of MEAL.

RedR- RedR are currently adapting some of the face-to-face teaching on M&E for online use.

COVID-19 M&E resources:

WHO COVID-19 M&E Framework - This is a general framework not specific to hygiene or preventative projects.

Doing fieldwork in a pandemic - This is a guide to social research methods. It focuses mainly on settings where technology access is high.

Behavioural and social drivers of vaccination: tools and practical guidance for achieving high uptake: This presents a range of tools to understand what drives uptake of vaccines through communicating what data sources to collect, how to analyse, plan, monitor and evaluate vaccine programmes.

CartONG overview on how to adapt monitoring during the COVID-19 pandemic - This detailed document is designed with humanitarians in mind and provides an overview of key principles for remote data collection and practical considerations for remote methods.

Editors notes

Authors: Matt Freeman

Reviewers: Peter Winch, Katie Greenland, Karine Le Roch

Version date: 28.5.2020