A PDF version of this brief is available for download here.

What is in this brief?

The brief is focused on hand hygiene. We have long understood the importance of hand hygiene for the reduction of diarrhoeal diseases, respiratory infections, hospital-acquired infections and during outbreaks like cholera and Ebola. Hand washing with soap or alcohol-based hand rub is an effective COVID-19 prevention measure along with physical distancing and appropriate mask use. Despite the many benefits of hand hygiene, actual practice remains low globally. The COVID-19 pandemic has already led to short-term improvements in hygiene behaviour but it is now critical to translate these improvements into longer-term handwashing habits and policy change so that the immediate threat of COVID-19 is addressed and progress can be made to reduce the burden of other faecal-oral diseases.

10 key lessons

In this brief, we present 10 key lessons gleaned from the work of the COVID-19 Hygiene Hub. These insights emerged from hundreds of informal conversations that we have had with programme implementers across 60 countries between April and October 2020.

Changing handwashing behaviour

10 key lessons from COVID-19 response | Actions to improve long-term handwashing behaviour and hygiene programming |

1. Pre-pandemic knowledge about how to change hygiene behaviours is still relevant. | Before you start a new programme, or adapt an existing one, learn from global evidence and the experiences of other local actors. |

2. Disease information alone is insufficient to change hand hygiene behaviour. | Identify a range of handwashing behavioural determinants and design hygiene promotion activities that directly address behavioural barriers. |

3. Investing in hygiene facilities makes handwashing easier to practice. | Hygiene programmes should prioritise improving access to convenient and desirable handwashing facilities with soap and water, and develop a plan for sustainability of such facilities from the outset. |

4. A range of delivery channels is needed to effectively and safely reach populations. | Map out all of the ways you could engage your population and select a set of delivery channels that will enable effective reach and can be used in a way that is acceptable, credible and persuasive. |

Effective programme design

5. Systematic programme design, based on behavioural theory, is still possible in outbreaks. | Use a behaviour change framework to guide each stage of your programme design. This will minimise preconceived biases, and allow you to create innovative, context-adapted activities. |

6. Plan how you will target and engage vulnerable groups early on. | Identify who your programme aims to reach and break this into population sub-groups if necessary. Work with vulnerable groups to design programmes that can benefit them equally. |

7. Develop a monitoring and evaluation strategy early on. | Develop a theory of change describing how you anticipate behaviour will change because of your programme. Develop indicators across this theory of change so that you can understand whether you had an impact and why. |

8. Programme adaptation is necessary on an ongoing basis. | Plan for adaptation by regularly discussing your programme with communities, stakeholders and implementation staff and adjusting activities accordingly. |

Strengthening the hygiene sector

9. New ways of collaborating are necessary to welcome and sustain the involvement of new actors. | Coordination mechanisms should have a clear strategy (grounded in behaviour change), effective leadership, and agreed on ways of sharing and collaboration between partners. |

10. Become more effective at learning, sharing and advocating for long-term change. | Build evidence generation into all programmes and share both successes and failures. Use this strengthened understanding of hygiene and behaviour change to advocate and drive change. |

What is the COVID-19 Hygiene Hub?

The COVID-19 Hygiene Hub is a free service to help actors in low- and middle-income countries (LMIC) share, design, and adapt evidence-based hygiene interventions to combat COVID-19. Since starting in April 2020, the Hygiene Hub has provided rapid technical advice and project support to more than 132 different organisations across 60 countries and developed over 40 long-term partnerships to support global or national-level initiatives. Over 250 projects from 70 countries have been shared on our interactive map, along with 20 in-depth programme case studies that document the successes and challenges of COVID-19 response actions. The global nature of our work puts us in a unique position to understand common challenges and identify innovative solutions to strengthen longer-term hygiene promotion.

Image: The Hygiene Hub’s interactive map shows COVID-19 programming across the globe.

Changing handwashing behaviour

Lesson 1: Pre-pandemic knowledge about how to change hygiene behaviours is still relevant

Hand hygiene programmes are more likely to be effective if they are designed to address behavioural determinants of handwashing; the factors that enable or prevent hand hygiene from being practiced in a particular context. When the COVID-19 pandemic hit, many response organizations focused on the unknowns around coronavirus transmission, and forgot about the wealth of information we already had on the global and context-specific determinants of hand hygiene.

Image: Handwashing is influenced by a wide range of behavioural determinants. Image by LSHTM

Unlike other COVID-19 prevention behaviours – such as mask use or physical distancing – we already knew quite a lot about the effectiveness of handwashing and handwashing behaviour change before the outbreak. Ignoring this created programme delays or led to the implementation of programmes that were not as evidence-based and context-adapted as they could have been. This is not a new phenomenon – similar results were found during the Ebola outbreak in West Africa.

COVID-19 did clearly have an effect on hygiene behaviour. Fear and risk perception were heightened and social norms changed. Together these factors make people want to wash their hands more frequently - just as we have seen during previous outbreaks. However, most of the other physical and social barriers to handwashing will have been unaffected by the pandemic and these determinants will still need to be addressed in order to improve hygiene behaviour.

For future outbreak responses, we should first make use of existing evidence and behavioural theory to guide immediate action. This prevents delays while allowing sufficient time for response actors to learn from communities and understand how behaviour has shifted. These insights can then be used to refocus and adapt interventions.

Key Action for improved programming: Before you start a new programme, or adapt an existing one, learn from global evidence and the experiences of other local actors.

Lesson 2: Disease information alone is insufficient to change hand hygiene behaviour

In the last few years, there has been a shift away from hygiene promotion activities that focus primarily on conveying information about health and disease. Most people across the world already understand the link between hand hygiene and disease, so telling them again merely reinforces what people already know. Hand hygiene is often practised semi-subconsciously as part of a routine or habit, and these can be more powerful drivers of behaviour than knowledge or beliefs.

Dissemination of disease information does play a more important role when a new pathogen emerges. For example, we promoted different key moments for handwashing to prevent COVID-19 than we typically would for diarrhoeal diseases. Information about disease transmission and symptoms was also essential to promote health-seeking behaviour, quell misconceptions, and help people understand this new pathogen.

However, it’s important to think beyond messages about disease and risk for several reasons:

Health messages typically become uninteresting over time. Hygiene Hub users have often described this as ‘COVID-19 fatigue’. For example, Oxfam is using a Community Perception Tracker to document community attitudes and concerns around COVID-19 in 9 countries. They’re finding that many populations are tired of programmes that only give COVID-19 messages because the pandemic is one of many issues they are facing.

COVID-19 programmes that positioned hygiene and other prevention behaviours as the ‘right’ or ‘altruistic’ thing to do to protect others have been more effective than programmes which only provide information. The same seems to be true for messages that remind people about how behavioural norms have changed.

Providing too much information about hygiene behaviours can actually have a negative impact. For example, a study in Bangladesh found that if handwashing messages are too complex they are harder for people to recall and practise.

Most people now know about COVID-19 and recognise handwashing as a preventative action. However, as people become less worried about COVID-19, handwashing rates may start to decrease, as has been seen in prior outbreaks. Therefore, we need to start adapting programmes so that they address a broader range of behavioural determinants.

Key Action for improved programming: Identify a range of handwashing behavioural determinants and design hygiene promotion activities that directly address behavioural barriers.

Lesson 3: Investing in hygiene facilities makes handwashing easier to practice.

The COVID-19 pandemic has shown that access to handwashing facilities, soap, and water is essential to improving hygiene behaviour. It can act as a reminder to wash hands, and makes regular handwashing more likely to be practised. Unfortunately, two out of five people globally do not have access to handwashing facilities with soap and water at home.

Image: A map showing coverage of handwashing facilities with soap and water – Brauer et al. 2020

The pandemic has driven community-led and institutional efforts to dramatically scale up universal access to handwashing facilities. This is true in households, schools, and health care facilities, but also in settings where hygiene has previously been overlooked such as workplaces, prisons and jails, refugee, migrant and other camp-like settings, care facilities, markets and food establishments, transport hubs, places of worship and other public spaces. Some of these innovations are captured and shared in handwashing compendiums developed by the Sanitation Learning Hub, WaterAid and UNICEF.

Image: Maggie Rarieya, Head of NBCC Secretariat demonstrates the proper handwashing technique at a handwashing station installed by Rotary Club of Kenya in collaboration with SHOFCO in Kibra, Nairobi County

However, we must also consider long-term maintenance of facilities and ongoing provision of soap and water, or new facilities could rapidly become non-functional. We still have lots to learn about how to ensure the sustainability of public handwashing infrastructure, but we have seen steps in the right direction. For example, the National Business Compact on Coronavirus in Kenya brings together a network of private sector actors to accelerate COVID-19 preventative action. So far, they have installed more than 5000 handwashing facilities and are currently undertaking research on the maintenance and sustainability of these facilities.

We have also seen organisations prioritising handwashing stations that are desirable to use and which actually cue handwashing behaviour. For example, the Hygiene Hub worked with the WASH in Schools Network to develop a guide on how to use behavioural ‘nudges’ to change handwashing behaviour in schools. In Zambia, WaterAid developed stickers which could be placed on the ground in public settings to point people towards their nearest handwashing facility.

Image: A sticker designed by WaterAid Zambia to guide handwashing behaviour in public settings

Key Action for improved programming: Hygiene programmes should prioritise improving access to convenient and desirable handwashing facilities with soap and water, and develop a plan for sustainability of such facilities from the outset.

Lesson 4: A range of delivery channels are needed to effectively and safely reach populations.

As in-person interactions reduced, many organisations had to fundamentally change the delivery channels they used to reach communities.

In the early stages of the pandemic, several organisations were able to take advantage of their previous experience with mass and social media to address hygiene programming. For example, in Burkina Faso and in several other countries, Development Media International were able to utilise their existing relationships with Ministries of Health and radio stations to quickly get on air with a range of innovative COVID-19 radio spots in different languages. We also saw a lot of local-level innovation, whether this was health volunteers using their expertise to influence others on social media or exploring how new technologies could enhance community sharing and action.

Image: Development Media International recording radio spots.

A family in India listen to COVID-19 stories on their mobiles. Gram Vaani Community Media used a mobile-based IVR (Interactive Voice Response) system that allowed community members to call a free number and leave a message about their community’s experiences with COVID-19. Users could also listen to messages left by others, and listen to relevant guidance from the WHO and national governments. The process allowed communities to feel connected, while also accessing correct information on COVID-19.

At the Hygiene Hub we have received numerous questions from users about the effectiveness of one delivery channel compared to another. While it is useful to think about the strengths and weaknesses of each medium, there is no universal answer to these questions. The reach of any given delivery channel will vary by context and it is necessary to map potential delivery channels accordingly. For example, a study in Cox’s Bazar in Bangladesh found that there were substantial differences between refugee populations and host communities in how likely they were to find certain sources of information trustworthy. These insights were used to inform the selection of delivery channels in both settings. Lastly, it is important to remember that the delivery channel itself cannot change handwashing behaviour. Content and appropriate framing of messages are the most important drivers of change, particularly when informed by behavioural insights.

Key Action for improved programming: Map out all of the ways you could engage your population and select a set of delivery channels that will enable effective reach and can be used in a way that is acceptable, credible and persuasive.

Effective Programme Design

Lesson 5: Systematic programme design, based on behavioural theory, is still possible in outbreaks

In the early days of the pandemic there was enormous pressure on governments and organisations to take immediate action. This pressure commonly resulted in organisations compromising key stages of the programme design process, something that has been observed in prior outbreaks. In hindsight, this perceived ‘urgency to act’ was often partially self-imposed, and did not always reflect either the emerging epidemiology or the feasibility of doing effective hygiene behaviour change at scale. Our Hygiene Hub case studies have highlighted that actual action was often delayed much longer than response actors envisaged, often due to administrative or financial delays.

To overcome these challenges, we observed many actors taking a phased approach to programme design. For example, Wash’Em released a list of 5 low-cost, easy to implement handwashing promotion activities during the first phase of the response and then, once implementation of these was underway, they recommended using their rapid assessment tools to contextualise and further adapt the programme.

Images: Oxfam using the Wash’Em approach in the Philippines to understand motivations related to handwashing behaviour. The Wash’Em work they undertook was part of a project funded by Unilever/DFID and delivered by Oxfam, in partnership with Philippine Rural Reconstruction (PRRM) Movement for Eastern Samar in Visayas, the Initiatives for Dialogue and Empowerment through Alternative Legal Services (IDEALS) and United Youth of the Philippines-Women (UNYPHIL-Women) in Mindanao.

Even though applying a systematic process to understand handwashing behaviour can take time and staff resources, it doesn’t have to be complex. It is normally a worthwhile investment because the final programmes are more likely to be effective and acceptable. Existing frameworks and theories can help - they typically provide tools which allow practitioners to assess a range of behavioural determinants rather than making assumptions about what factors are likely to be most influential. Many frameworks also outline Behavioural Change Techniques which can help practitioners translate insights about behaviour into activities that address barriers or enablers of handwashing.

For example RANAS Ltd., UNHCR, World Vision and the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation (SDC) applied the RANAS approach to their response programming within a refugee camp in Zimbabwe. The qualitative and quantitative assessments took several months when done alongside other activities but ultimately led to practical behavioural insights and an innovative context-adapted programme.

Image: A World Vision fieldworker conducting a RANAS interview about handwashing behaviour.

Key action for improved programming: Use a behaviour change framework to guide each stage of your programme design. This will minimise pre-conceived biases, and allow you to create innovative, context-adapted activities.

Lesson 6: Plan how you will target and engage vulnerable groups early on.

Curbing the impact of COVID-19 requires everyone to adopt preventative behaviours. However, the populations at risk of severe COVID-19 are very different to our typical programme targets for diarrhoeal disease (children under 5 years of age and their parents). We have therefore needed to improve our ability to engage clinically at-risk populations (such as older people and those with pre-existing conditions) as well as identifying populations with high risk of exposure to the virus because of where they work or live (such as people living in informal settlements, camp settings, prisons and care homes and people working in health care, public transport and service delivery). The COVID-19 pandemic has also reminded us that existing inequities within societies mean many people are disproportionate vulnerable to secondary impacts of the disease (such as people working in informal sectors, living in crisis-affected regions and populations with limited socio-economic mobility). To change the behaviour of these diverse groups, we need to learn from organisations representing vulnerable groups, make programming inclusive from the outset, and use new media creatively.

During the early stages of the response, the focus was on reaching everyone predominantly through mass or social media. However, we now recognize that these blanket approaches to COVID-19 prevention and hygiene promotion are not reaching certain sub-groups of the population. The increased use of technology can easily exclude certain groups. For example, globally, mobile phone access is lower among women, people with disabilities, older people and people living in rural areas. To effectively reach these groups, many organisations are working via key community stakeholders and building local support networks. WaterAid took a systematic approach to thinking about inclusion within their response programming. Early on during the pandemic, they developed a simple set of Do’s and Don’ts for making sure inclusivity was mainstreamed into COVID-19 response programming. WaterAid then used their COVID-19 communication materials to make sure information was accessible to all, to challenge gender stereotypes and to normalise the role of people with disabilities in society.

Image: A still from a TV advert created by WaterAid Ethiopia which includes a sign language interpreter

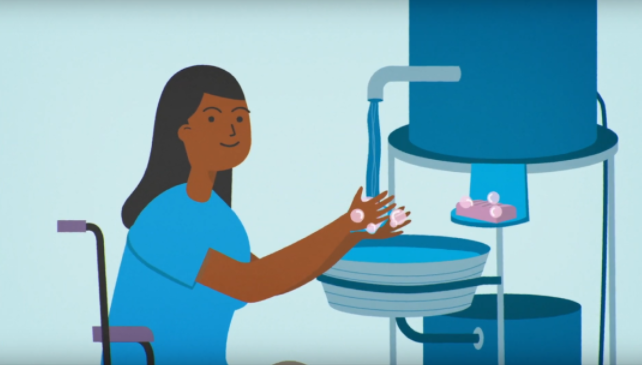

Image: A still from a WaterAid standard handwashing promotion and includes depictions of people with disabilities and older people washing their hands.

Key action for improved programming: Identify who your programme aims to reach and break this into population sub-groups if necessary. Work with vulnerable groups to design programmes that can benefit them equally.

Lesson 7: Develop a monitoring and evaluation strategy early on.

As we transitioned out of the acute phase of the COVID-19 response, the Hygiene Hub received a flurry of questions about how to effectively measure handwashing behaviour and the impact of hygiene behaviour change programmes. Handwashing behaviour is notoriously hard to measure, and the COVID-19 pandemic has made it even more challenging. For example, some of our most reliable measures such as household observation are no longer safe to conduct in most settings. We are also no longer just interested in measuring handwashing behaviour in households, but also in other public settings.

To overcome this, many organizations have found it useful to fully articulate the theory of change underlying their intervention and assess progress against this through a range of qualitative and quantitative methods.

Many organisations also experienced steep learning curves as they moved towards remote data collection methods (such as phone-based interviews or surveys), as even setting up remote data collection processes took time. For example, for remote phone surveys, organisations had to spend time collecting phone numbers from the target communities before any data collection could begin. This process often created sampling biases and excluded some groups. Organisations reported that learning remotely from communities was much more challenging than face-to-face interactions – it was harder to build rapport with participants on short phone calls. Actors subsequently reported low response rates and many interrupted surveys due to connection issues and limited phone credit and electricity.

To compensate for these challenges many organisations are using multiple data collection methods. In particular, we have seen a number of organisations conducting observations at recently installed public handwashing facilities. For example, in Indonesia UNICEF supported the government in establishing a nationwide monitoring system to provide real-time behavioural insights. They are working with a network of 30,000 volunteer monitors who document handwashing behaviour in public locations over the course of a 10-minute window.

Key action for improved programming: Develop a theory of change describing how you anticipate behaviour will change because of your programme. Develop indicators across this theory of change so that you can understand whether you had an impact and why.

Lesson 8: Programme adaptation is necessary on an ongoing basis

Programming during the pandemic has largely been a story of adaptation. We have seen many existing health programmes pivot and adjust their programmes to be more COVID-19 sensitive. For example, one of our Hygiene Hub case studies explains how the National Sanitation Campaign in Tanzania was able to leverage its reach and the capacity of local teams to rapidly incorporate COVID-19 prevention messages. The Hygiene Hub has also supported and learned from actors in a range of other sectors (such as trachoma prevention, nutrition programming and educational service provision) as they pivot their programming to be more COVID-19 sensitive.

Images: Social Media posts from the campaign in Tanzania. It features everyday people, such as local tuk-tuk drivers (left) and celebrities such as Sylvia Mkomwa (right), a finalist in the 2017 Miss Universe Tanzania competition to promote unity and action. The “U” shape symbolises two people standing apart (physical distancing) but joined together in a collaborative effort to fight the virus.

Programmes have needed to adapt in line with the changing dynamics of transmission, national guidelines, new evidence and changing local perceptions. While the changing situation could easily have led to chaotic programming, we have seen many organisations adopt a systematic process to assessing risk and adapting programmes in response (such as adapting programme delivery if transmission rates increased). Organisations also had to set up new mechanisms for ongoing learning and feedback from communities. This real-time feedback allowed programmes to be adjusted to address emerging community perceptions.

Images: Action Contre la Faim set up a range of mechanisms to ensure continuous learning from communities. In Iraq and Jordan they used phone calls to communicate with target populations. The image on the left shows Zeina Algharaibeh in ACF Jordan listening to the opinions of populations via their phone service. In Sierra Leone (right) they set up physically distanced question and answer sessions to address common concerns and address misinformation.

Lastly the pandemic has caused us all to adapt at an organisational and individual level. Most response actors have been just as impacted by the pandemic as the populations they aim to serve. Organisations have had to put in place measures to maintain staff safety and wellbeing, while also allowing flexibility in ways of working to allow for the fact that at any given time multiple staff may be sick or infected with COVID-19 and have to isolate. Replacing staff members, even temporarily, can force organisations to adapt their programmes, sometimes at very short notice.

Key action for improved programming: Plan for adaptation by regularly discussing your programme with communities, stakeholders and implementation staff and adjusting activities accordingly.

Strengthening the hygiene sector

Lesson 9: New ways of collaborating are necessary to welcome and sustain the involvement of new actors.

The scale of the COVID-19 pandemic is unprecedented. Responding effectively would clearly have been too much for any one government or organisation to take on. Instead, we have seen many new actors becoming involved in handwashing promotion or giving it much greater priority. As new actors come on board, it is important that we actively work to minimise any duplication of efforts. Organisations with many years of hygiene expertise need to accommodate newcomers to the sector and share learning with them. For example, in some countries we have seen organisations extending training and capacity building sessions that would normally be run just for their staff to other organisations in their region. These kinds of collaborations will help new actors to avoid common pitfalls.

The private sector has also provided a critical role in the response in many countries. For example, Unilever have worked with the UK’s Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) to provide £100 million in funding to a network of response organisations.

Equally, it is important that organisations working on hygiene do not get too stuck in a ‘behavioural bubble’. During outbreaks, handwashing is rarely the primary concern of our target populations. Indeed it is anticipated that in LMICs the toll of secondary socio-economic and health impacts may be greater than that of the disease itself. Overcoming this requires us to work closely with colleagues in livelihoods, protection, education, mental health and nutrition. For example, the hygiene team at IOM in Ethiopia worked with their Mental Health and Psychosocial Support (MHPSS) colleagues and local artists to create a COVID-19 colouring book for children that covered both mental health and hygiene topics.

Image: The front cover of the mental health and hygiene colouring book created by IOM in Ethiopia.

In several countries we have also seen organisations work with communities to set up soap manufacturing businesses – something which can support livelihoods while meeting local hygiene needs. Improved hygiene requires equitable water access for all, and in many countries this has prompted hygiene actors to work with governments and water providers to waive water bills or provide water subsidies during the pandemic.

At a national level, we have seen new mechanisms spring up to coordinate hygiene action. In some cases, this has fallen within the mandate of newly established Risk Communication and Community Engagement (RCCE) working groups. In crisis-affected settings, hygiene working groups within the Global WASH Cluster are being established or strengthened. The Global Handwashing Partnership has developed guidance on setting up national or sub-national handwashing partnerships. Remote working has actually allowed a more diverse set of hygiene stakeholders to contribute to these coordination meetings, since those who were geographically distanced are now just a call away.

Many of these coordination mechanisms initially focused heavily on standardising messaging in the early phases of response. Now we are seeing coordination mechanisms shift gears, revise their strategies and focus more on supporting long-term sustainable hygiene behaviour change.

Coordination mechanisms seem to work best when there is effective leadership, trust between partners and regular sharing of timely information. For example, in Nigeria RCCE coordination was spearheaded by the Nigerian Presidential Task Force who used weekly polling to gain insights into what messages are reaching citizens, how effective they are at changing behaviour and to identify concerns and issues rising from the population.

Key action for improved programming: Coordination mechanisms should have a clear strategy (grounded in behaviour change), effective leadership, and agreed ways of sharing and collaboration between partners.

Lesson 10: Become more effective at learning, sharing and advocating for long-term change.

Since April 2020, the Hygiene Hub technical team have learned a great deal from all of our users. We have also been able to promote cross-learning between organisations and governments. For example, within the space of two weeks we had four organisations contact us regarding hygiene promotion and COVID-19 messaging in schools. We were able to connect these organisations so that they could review each other’s materials and learn from each other. Similarly, we have been working with Governments and local partners in Sudan and Ethiopia to develop targeted approaches to protect high risk individuals. This experience allowed us to draw parallels between the challenges and opportunities in both settings and more effectively inform national strategies.

In recent months, we have seen a shift in thinking across the sector. Governments and organisations are now focusing on how we can channel the current momentum around hand hygiene into long-term sustainable change. Progress towards this is being championed by the WHO and UNICEF-led Hygiene for All initiative, of which the Hygiene Hub is a core partner. The initiative sets out plans to support countries as they respond to the COVID-19 pandemic, while also developing national hygiene roadmaps to rebuild and reimagine the state of hand hygiene for the future.

One of the Hygiene Hub’s roles within the Hygiene for All initiative is to continue to share case studies of effective hygiene programming. We will also undertake a comprehensive review of the evidence around all aspects of hand hygiene to identify knowledge gaps and begin to formulate a research agenda for the sector.

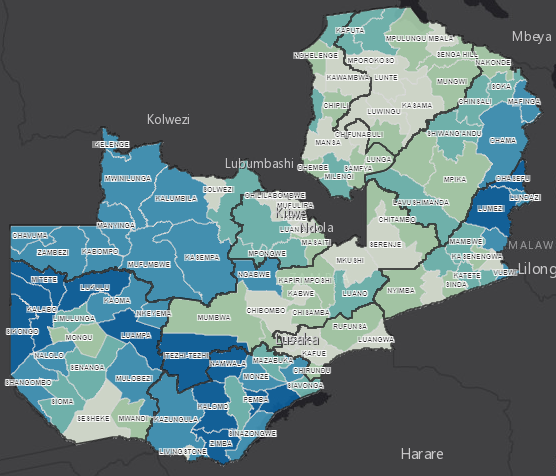

Evidence synthesis can be a key tool in advocating for long-term change. For example, in Zambia, GRID3 have been working with the Government and implementation partners to develop a dashboard of geo-specially mapped risk factors and response actions. They have then worked with local government representatives to use the data to advocate for change.

Image: GRID3’s work to geospatially map WASH associated risks in Zambia is contributing to improved planning and policy.

In South Africa, pre-pandemic advocacy efforts from a range of actors had led the Government to adopt a Hand Hygiene Behaviour Change Strategy for 2016-2020. When the pandemic hit, the principles of this strategy played a key role in positioning hand hygiene as core part the national COVID-19 response. Now local partners are working to develop the next strategy which will build on the limitations of the past strategy and the current moment around hand hygiene.

Key action for improved programming: Build evidence generation into all programmes and share both successes and failures. Use this strengthened understanding hygiene and behaviour change to advocate and drive change.

Want to learn and share more about COVID-19 Hygiene response programmes?

Browse our website: www.hygienehub.info

Check out our case studies and resources in a range of languages. Contact us if you would like your work featured in a Hygiene Hub case study.

Add your COVID-19 project to our interactive map by completing this form.

Have a discussion with one of our 45 technical advisors in real time via our website or send us an email at support@hygiene.hub.info

This brief was written by Sian White (LSHTM) who coordinates the Response Team within the Hygiene Hub. Valuable inputs were provided by Robert Dreibelbis (LSHTM), Peter Winch (Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health), Katie Greenland (LSHTM), Claire Collin (LSHTM), Yolisa Nalule (LSHTM), Jenala Chipungu (Centre for Infectious Disease Research, Zambia), Joanna Esteves Mills (Hygiene for All initiative, UNICEF), Bruce Gordon (WHO), Kondwani Chidziwisano (University of Malawi / WASHTED), Foyeke Tolani (Oxfam) Astrid Hasund Thorseth (LSHTM), Ana Hoepfner (CAWST), Alexandra Czerniewska (LSHTM), and Sarah Bick (LSHTM).

Published on Global Handwashing Day, October 15th, 2020.

White, Sian; (2020) Learning Brief: What have we learned about promoting hand hygiene during the COVID-19 pandemic? London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, London, UK. DOI: 10.17037/PUBS.04661690

Link: http://doi.org/10.17037/PUBS.04661690