Does my organisation need to consider the ethical implications and risk of data collection during infectious disease outbreaks?

Whenever you plan to collect data, whether for a research study or for monitoring and evaluation (M&E) purposes, you should always approach it with an ethical mindset. This means actively reflecting on the ethical issues that may arise throughout the whole process of data collection and thinking about whether your plans are appropriate and acceptable; starting from the initial design and planning of the work and continuing right through to the data analysis, reporting and dissemination phases.

To help ensure that planned data collection is ethical, many organisations produce their own guidelines. This may include checklists of dos and don’ts which set out the practical steps you should take to make sure that your work is ethical. If these guidelines are not available in your organisation or further guidance is needed, there are also many tools available online to aid organisations in ethical data collection, including this Hygiene Hub resource and this ALNAP report.

The primary purpose of all ethical guidelines relating to data collection is to protect the participants who are involved in the data collection from harm and to ensure that the data collected is credible and useful. It is also important, particularly during disease outbreaks, to protect data collectors from unnecessary risks.

Some things to take into consideration when carrying out any data collection include:

Why is the work useful, necessary and feasible?

To whom is the work useful, necessary and feasible?

Why does the work need to be done now, here and with this community?

Does the work need to be done by our organisation? If not, how can we establish structures, so that in future, those who should be leading the work can do so?

In what ways has the community been engaged about this project? How will this continue during the project?

How can the design and conduct of the work be sensitive to the cultural, socioeconomic, environmental and political context?

How can robust safeguarding policies and processes be put in place?

How might the work put participants at additional risk? How can robust processes be put in place to manage and mitigate risks and maximise benefit?

Can identity and data be protected and secure? This should include ensuring identity and confidentiality are protected across all data collection activities, from data collection, storage, analysis and reporting, as well as when data is shared between collaborators.

Is participation based on informed voluntary consent?

Does the method and implementation respect people’s rights and dignity?

Will the findings be maximised to improve programming and understanding?

How will you share the findings of your study with the research participants?

Do I need to obtain formal ethical approval for my data collection?

If you are planning to collect operational data that will be used only internally as part of your organisation’s standard M&E activities to improve a specific practice or programme – i.e. you are not going to publish the data or the findings – then you do not need to obtain formal ethical approval from external review boards. However, you may still need to obtain permission to access certain places or populations and these applications should address any relevant ethical concerns. As outlined above, even if you do not need to obtain formal ethical approval, your project should still undergo a process of ethical reflection and planning.

If you are getting involved in a research project with the intention of gaining generalisable knowledge or publishable results then ethical approvals will need to be in place. In this instance, relevant protocols should be submitted for review. Research protocols can be submitted to the Institutional Review Boards (IRB) or Research Ethics Committees (RECs) at universities or within government departments. Even if you are collaborating with a research institution based in another country that will be getting ethical clearance from their REC, it is important to also get ethical clearance in your country. You can find detailed ethical guidance for research, evaluation and monitoring activities from the FCDO here. If your organisation is not planning to submit for formal ethics approval, it is still useful to think through the criteria set out in guidance like this. Seeking formal ethics approval is not the end of the ethics process - it is just the start. It is designed to encourage you to think through all the ethical aspects of your data collection so that you can put these principles in place throughout your work.

What tools are available to aid organisations in acting ethically while learning from communities?

The following documents outline ethical challenges of conducting research in emergencies, including during outbreaks and for disease surveillance. We have also included links for COVID-19 specific guidance. Although the first two tools below are designed with researchers in mind, many of the recommendations are also applicable to M&E approaches used by programme implementers.

The Research Ethics Tool by Elrha has been designed to help researchers think through ethical issues that may arise while undertaking research in crises. It includes recommendations and considerations for each stage of the design, implementation and dissemination of research.

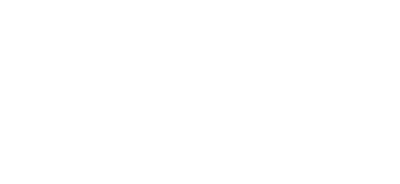

The Research in Global Health Emergencies report by the Nuffield Council on Bioethics aims to identify ways in which research can be undertaken ethically during emergencies. It includes an ‘ethical compass’ to help users think through ethical dilemmas arising during research (see figure 1).

The WHO guidelines on ethical issues in public health surveillance aims to help everyone involved in public health surveillance, including officials in government agencies, health workers, NGOs and the private sector, navigate the ethical issues presented by public health surveillance.

The WHO has also published guidance for COVID-19 research: Ethical standards for research during public health emergencies: Distilling existing guidance to support COVID-19 R&D. The document summarizes key universal ethical standards to ensure ethical research during the COVID-19 outbreak.

This document by the UK Collaborative on Development Research (UKCDR) emphasizes the importance of safeguarding in research during the COVID-19 pandemic and outlines specific issues to consider during the current crisis. It also signposts additional useful resources.

Ethical Compass: 3 Core Ethical Values. Source: Nuffield Council on Bioethics (2020).

Note that the diagram uses the term “research” but this ethical compass is relevant to all data collection activities.

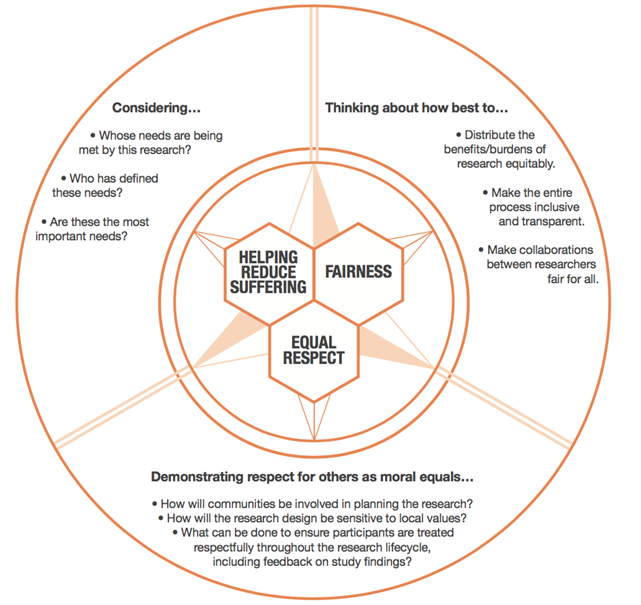

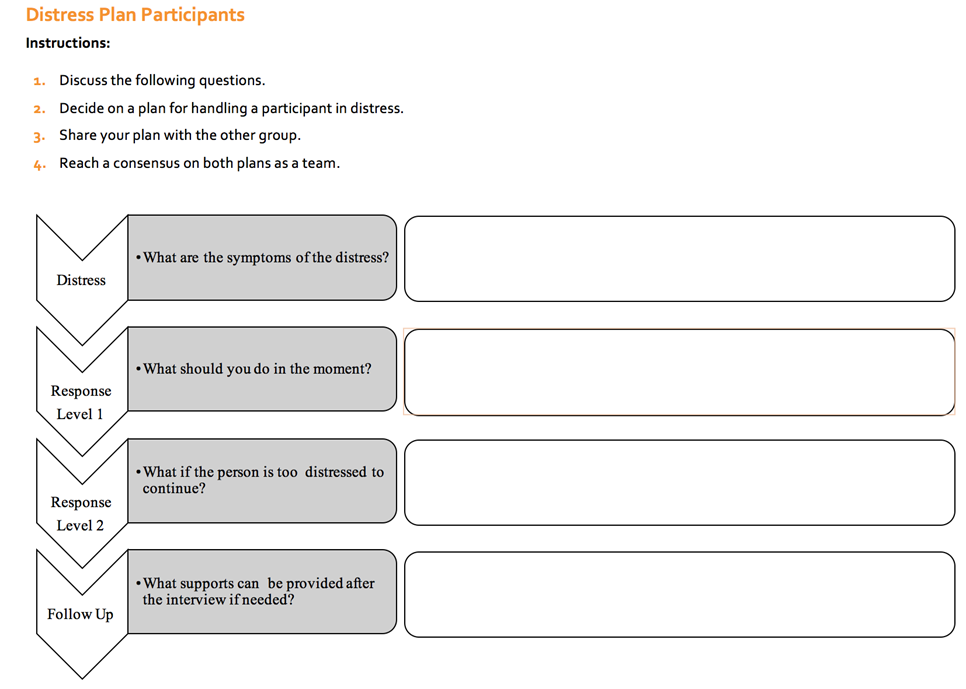

It is likely that people who participate in research or standard M&E processes during outbreaks may be experiencing economical or social hardships due and in some cases, that they have recently lost a loved one. Data collection processes must be designed with this in mind and data collection teams should have plans in place to manage and support participants who are distressed. “Distress planning” should include identifying support mechanisms or services to which participants can be referred. Note that some RECs will ask for a detailed plan of how participants will be engaged in data collection, especially regarding sensitive topics. The Wash’Em project has developed a tool to aid data collection teams with distress planning.

Below is an example of the questions you should consider prior to working with participants. Note that that tool also includes distress planning for data collectors (here termed ‘interviewers’), which is also an important consideration.

Distress plan for participants. Source: Wash’Em

Distress plan for interviewers. Source: Wash’Em

This blog by 3ie outlines some specific points that should be considered while collecting data from people during outbreaks, focusing on COVID-19. These considerations are designed to minimise the potential unintended consequences of collecting data during the pandemic and include:

Will the data collection benefit the community? Think about how participating in the data collection could benefit participants directly (e.g. being remunerated for their time or indirectly, by improving response programming in their area). Let participants know how findings will be used and shared, including with them.

Will you be (falsely) raising expectations as a result of the data collection? For example, your data collection may raise expectations in relation to services that might ensue or perceived increased entitlement to services. Think about how you can mitigate against this and be clear and transparent.

How will you ensure informed consent? Data being collected remotely requires even clearer explanations for why it is being collected and how it will be used.

How will safety concerns related to disease transmission be monitored to protect participants and data collectors? This is especially important if data is being collected in person in an area with community transmission of the infectious disease.

Can you offer respondents compensation for their time? During outbreaks, people in low-and-middle-income countries may lose their jobs and livelihoods, increasing stress within the household. Where possible, consider providing compensation for participant’s time. If you are compensating participants, it is important to ensure that it does not become coercive or manipulative, especially if there are any risks associated with the activity. If providing incentives, consider where this may create unhelpful precedents for other organisations working in the area and where possible, try to collaborate with the government and other organisations to make decisions on this.

How long will the data collection take? If remote phone-based data collection is being done, respondents may need their phones to communicate with others and receive information about the outbreak, so surveys should not take too long. It is important to give respondents accurate estimates of how long all aspects of the data collection will take. Respondents also have other urgent priorities in their lives, including income-generating activities or caring responsibilities which should also be taken into consideration. Additionally, respondents may share their phone and may not have access to electricity to charge their phones regularly. Consider how you can support with inputs during data collection, such as air-time and mobile phone solar chargers.

Are questions you ask likely to create tensions within households? Consider the fact that domestic violence increases during lockdowns and that the survey should not create more risks by keeping respondents on the phone too long or asking contentious questions. Note that even the general topic of the public health risk of concern could be enough to create tensions, regardless of what the questions involve. Think through options to mitigate this risk.

You may also want to consider whether your data collection team has an ethical duty to provide disease related information to participants. If so, this can be done after the interview or survey so as not to bias results. Consider whether you may need to provide participants with the following kinds of information:

Providing information about preventive behaviours - train and instruct your data collection team to give participants information about the precautions they can take to protect themselves against the disease in question. Depending on the mode of transmission, this could include information on handwashing with soap and promoting behaviours related to physical distancing and mask use.

Debunking Myths - put systems in place to correct current misunderstandings and direct respondents to accurate sources of information. This is particularly important if, during interviews, it becomes apparent that people are reporting harmful practices (e.g. consuming bleach) or myths about disease transmission routes or causes.

Answering frequently asked questions (FAQs) - create an FAQ document and share this with your data collection team so that they can accurately answer questions emerging during data collection with participants.

Identifying services – compile a list of services in your local area and share this with the data collection team so that they can refer people to these services as necessary. This may include services providing food aid, mental health care or livelihood support.

How can we ensure that participants are truly informed when they consent to take part in a remote data collection activity?

Obtaining informed consent is as important for remote data collection as it is for other forms of data collection. However, given the limitations of the amount of time that a phone survey can last and difficulties understanding long and complex text read over the phone, a less-detailed and simplified informed process may be considered.

The informed consent process, however, should be considered as an iterative and on-going process. It may not be necessary to obtain consent afresh at every stage of the data collection (and this may not be applicable in, for example, a one-off phone survey). However, to aid understanding, you should provide participants with information throughout the data collection process and ensure that they are aware consent can be withdrawn at each stage of the process. This can be particularly important where new information becomes available that might impact the risks or benefits that the data collection poses.

Prior to obtaining consent over the phone, it is necessary to confirm that you are speaking to the right respondent. You should have a protocol of what to do if the person who answers the phone is not the agreed respondent. For example, if someone else answers the phone:

Ask the person responding if they know the target respondent and if this person is reachable through this number, or if they have the correct number for this person.

If they do not know the target respondent, apologise for the inconvenience, and end the call.

Informed consent should follow a standardised participant information sheet and, at minimum, describe the following (adapted from here):

Who you (the data collector) are and which organisation you are working for (restate even if mentioned when starting call).

Why you are collecting this data - i.e. what the overall purpose of the data collection is.

Why the respondent has been chosen - for example, explain if they have been randomly selected, or if they have been selected because they belong to a particular group you are targeting (e.g. a person over the age of 60).

That participation is voluntary and that choosing not to participate will not have any consequences for the respondent or their family. Clearly outline what respondents need to do in order to decline or withdraw their participation (e.g. tell them they can say something along the lines of “I do not want to continue the conversation”). Remind respondents again before seeking consent that they are free to decline and, at different stages of the data collection, remind them that they are free to withdraw their consent. Also state that once a respondent’s data has been anonymised and combined, it cannot then be excluded.

The approximate number of participants you will collect data from.

What the respondent will be expected to do if they agree to participate, including the expected duration of their participation.

Any reasonably foreseeable risks or inconveniences to the respondent related to participating in the data collection.

Any benefits a respondent may receive by participating.

How the data collected will be used and who will have access to this data.

How the respondents confidentiality and privacy will be ensured.

Who the respondent should contact if they have any questions and provide the relevant contact details.

Who the respondent should contact if they have a problem or a complaint regarding the data collection and the relevant contact details.

These things should be described in simple terms, in a language that the participant is fluent and comfortable in. As mentioned above, it is important to inform the respondent of how long the survey or interview will take. This will reduce incidences where the respondent has to cut the interview short due to competing priorities in their lives or phone batteries running low.

Once these things are explained, verbal consent should be requested and noted explicitly by the data collector. Verbal consent should be obtained by getting the participant to say ‘Yes, I agree’ to the following statements:

I confirm that I have understood the information for the study named “insert study name here”. I have had the opportunity to consider the information, ask questions and have these answers satisfactory? Do you agree to participate?

I understand that my consent is voluntary and that I am free to withdraw this consent, without giving any reason and without any consequence to me, up until the point at which data is anonymised or combined and therefore cannot be excluded. Do you agree?

I understand that overall data from the project may be shared publicly but that I will not be identifiable from this information (if applicable). Do you agree?

Avoid sensitive questions

When collecting data over a phone, it is important to remember that it is possible that the participant will be overheard by others in their own family, especially if physical distancing is being enforced and people are being encouraged to stay home. Therefore, we would recommend that mobile data collection be sensitive to this and avoid topics that might be associated with stigma, or which could put the participant at risk if others knew the information. Examples of such topics include mental health, domestic violence, sanitation behaviours and menstrual hygiene management. If you will be asking sensitive questions, consider checking first whether the person is alone and if it is OK to ask them questions in relation to your study (Yes/No responses). This can help avoid unintended harm and give the person an easy way to decline to participate if they feel at risk. If absolutely necessary, questions of this nature can be answered with simple multiple-choice responses (e.g. a scale from 0-10). Interviewers should also check with respondents that they are the only ones able to hear the phone call and also provide options to skip any questions, should they perceive any signs of the respondent being uncomfortable. Ascertain reason for refusal.

If participants refuse to take part you may want to ask the reason for refusal, so that this can be addressed directly or fed back and used to help improve future processes. This must be done very carefully - the data collector must stress that this is optional and in no means a way to push participation. If asking for this information, remember that a closed question (Yes/No response) might be easier for them to answer if the topic is sensitive and others might be listening at the other end. If the respondent refuses to give a reason, thank them for their time, record the refusal and the reason, reassure the respondent that there will be no consequences to their refusal and then end the interview.

Editor's notes:

Authors: Fiona Majorin, Julie Watson and James B. Tidwell

Review: Anne Harmer, Anna Skeels, Dr, Dónal O'Mathúna, Gautham Krishnaraj PhD(c)

Last update: 01.03.2023