How do diseases transmit via surfaces?

Infectious diseases can be transmitted through surfaces (see figure below). Surfaces can include a range of commonly touched objects such as tabletops, doorknobs, toys, light switches, and other objects. Generally speaking, the likelihood of disease transmission through surfaces depends on the following factors:

Amount of pathogen (virus) shed by infected individuals

Virus survival on surfaces

Rate of transfer from surfaces to hands and mouth/nose/eyes

Number of viruses required to cause disease (infectious dose)

Resistance of the virus to disinfection

This review provides a synthesis of the mechanisms involved in surface-mediated virus transmission, including evidence related to SARS-CoV-2 .

While SARS-CoV-2 transmission via surfaces is possible, the scientific evidence available to date suggests that the primary transmission route for SARS-CoV-2 is airborne (as outlined in this Lancet comment) and that contaminated surfaces present a low risk (as noted in this Science Brief by the US CDC).

Surface-mediated transmission. Adapted from: Julian, 2010.

What does “detection” mean when discussing viruses in the environment?

Viruses in the environment can be detected through multiple methods. Current approaches rely heavily on the use of molecular methods that detect unique genetic material for the pathogen of interest (in this case, SARS-CoV-2). Genetic material is just one component of a virus and cannot cause infection on its own. Genetic material can often be detected in both viable (“living”) and non-viable or inactivated (“killed”) viruses. Detection of the SARS-CoV-2 in the environment or on surfaces by molecular methods does not mean that the virus is still alive and capable of causing infections. The ability of the virus to infect a new individual will depend on a range of factors, including if the virus is viable.

How can surfaces get contaminated with SARS-CoV-2?

Surfaces can become contaminated with SARS-CoV-2 when someone infected with the virus (who may or may not have COVID-19 symptoms) releases the virus from their body into the environment, for example through coughing, sneezing, vomiting, or defecating.

In healthcare settings, SARS-CoV-2 genetic material was found on 8.9% of 336 sampled surfaces, mostly in individual bed spaces, in a multicentre study conducted in England. In another study (unpublished as of December 18, 2020) 13.1% of 336 sampled hospital surfaces (mostly those in direct contact with patients), were positive for the virus genetic material. In an isolation room occupied by a COVID-19 patient in Singapore, SARS-CoV-2 genetic material was reportedly detected on 87% of 15 room surfaces (including things like bed rails and windows) prior to cleaning. The same study found SARS-CoV-2 genetic material on 60% of 5 bathroom sites (including the toilet bowl, sink, and door handle). Other studies have found similar results in healthcare settings (Study 1, Study 2, Study 3, Study 4, Study 5).

In community settings, SARS-CoV-2 genetic material was detected at low concentrations in 8.3% of 346 samples collected from frequently touched surfaces in Somerville (MA, USA), with the highest positive rates on trash can handle and liquor store door handle (Study 6). The corresponding risk of infection was estimated to be low. Likewise, in another study in Belo Horizonte (Brazil, Study 7), 5.3% of 933 surface samples tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 genetic material, with a majority of those positive samples coming from public benches at bus stops or squares. These results are consistent with a small-scale investigation in a rural village in Spain (Study 8).

A systematic review of surface contamination studies suggested that laboratories had the highest proportion of surfaces testing positive for SARS-CoV-2 genetic material (Study 9). Across all settings, masks and eating utensils used by COVID-19 patients were most commonly contaminated with the virus, followed by electronic equipment (see table below).

Overall, while SARS-CoV-2 transmission via surfaces is possible, the scientific evidence available to date suggests that the primary transmission route for SARS-CoV-2 is airborne (as outlined in this Lancet comment) and that contaminated surfaces present a low risk (as noted in this Science Brief by the US CDC).

How long does SARS-CoV-2 survive on surfaces?

When an individual sheds viruses onto a surface or object by sneezing, coughing or defecating, these viruses will die off and the number of infectious viruses on the surface will decrease over time. SARS-CoV-2 can survive on surfaces for hours to days depending on surface type, temperature and humidity. Seven laboratory studies were identified in a recent systematic review that assessed the persistence of SARS-CoV-2 on surfaces: the resulting half-lives (time needed for the number of viruses to be reduced by 50%) were between 2.2 and 18 hours on stainless steel, nitrile and plastic surfaces. Factors influencing survival of coronaviruses on surfaces are discussed in at least two reviews (Study 1 and Study 2): they include surface porosity, environmental conditions, and characteristics of the viruses. The virus appears to be quite sensitive to heat and UV radiation, so if the surface is in the sunshine the virus may die more quickly.

To what extent can SARS-CoV-2 be transferred between surfaces and hands?

Not all viruses present on a given surface will be transferred to hands upon touching that surface. Transfer rate or transfer efficiency is a measure of how easy it is for microorganisms such as viruses to move from a surface or object onto hands. We do not know the exact transfer rate of SARS-CoV-2. However, transfer efficiencies tend to be lower from porous surfaces, like fabric, than from non-porous surfaces, like stainless steel. In a laboratory study which used a virus similar to SARS-CoV-2, roughly 5-20% of the virus was transferred from a hard surface to fingers. In comparison only 0.4% of the virus was transferred from porous surfaces to fingers. But SARS-CoV-2 might not behave like the virus used in this study. Even low transfer efficiencies can result in hand contamination with the virus if the virus exists in high concentrations on a surface.

What type of surface cleaning and disinfection should we promote for homes and workspaces?

This section draws information from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) guidance on household cleaning and disinfection and detailed disinfection guidance, the World Health Organization’s Interim guidance on Cleaning and disinfection of environmental surfaces in the context of COVID-19, Water, Sanitation and Hygiene Technical Brief and Interim guidance for home care of COVID-19 patients, as well as the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) Interim guidance for environmental cleaning in non-healthcare facilities exposed to SARS-CoV-2.

Infected individuals may shed SARS-CoV-2 even if they develop no or mild symptoms, and we know that the viral load of patients is highest when symptoms first appear. Therefore it is important to clean surfaces and objects in your home even if nobody appears sick in your household. Additional recommendations are provided below if a COVID-19 case occurs in your household.

What is the difference between cleaning and disinfection?

Cleaning typically refers to the physical removal of dirt and germs from surfaces, normally with soap or detergent and water, before disinfection. Disinfection is the process of inactivating (killing) germs like SARS-CoV-2 on surfaces, often by using chemicals such as chlorine (bleach) after cleaning.

Daily cleaning and disinfection of frequently touched household surfaces such as doorknobs, light switches, toilets, and faucets is recommended.

If surfaces are visibly dirty, they should be cleaned with water and regular soap/detergent prior to disinfection. Cleaning should be done systematically, from clean to soiled areas, and from high to low areas. Cleaning materials (cloth, gloves) can become contaminated and should be laundered (as described below) or disposed of safely.

What are the types of surfaces found in homes?

Household surfaces and objects can be porous or non-porous. A few examples are provided in the following table. Porous surfaces and objects have lots of very small holes that let liquid pass through, whereas nonporous surfaces do not. Because of this difference, recommended cleaning and disinfection practices are different for porous and non-porous surfaces.

Adapted from: National Pesticide Information Center

The WHO recommends identifying ‘high-touch’ surfaces in the household for priority disinfection. High-touch surfaces may include door, window, cabinet, and appliance handles, kitchen and food preparation surfaces, countertops, bathroom surfaces, toilets and flush handles, water faucets, and electronic devices such as phones, tablets, keyboards, and computer mice.

Non-porous surfaces

Commonly available disinfectants like household bleach can be used to disinfect non-porous surfaces after they have been cleaned. Household bleach usually contains 5-6% sodium hypochlorite (chlorine) and should be diluted with clean water before use to a final concentration of at least 0.1% chlorine (see diagram below for instructions). Please note that concentration of chlorine in bleach may vary by context, if it is lower than 5-6%, dilutions should be adjusted accordingly. For more information on creating chlorine solutions try this calculator.

Chlorine solutions are corrosive; they should never be stored in metallic containers and, in case of application onto a metallic surface for disinfection, thorough rinsing with water after disinfection can prevent corrosion. Alcohol-based disinfectants with at least 70% alcohol can be used as an alternative to chlorine for disinfection of metallic items and surfaces.

Chlorine can cause irritation to skin and eyes. People should be instructed to prepare dilutions in well ventilated areas and to avoid contact between the bleach/dilution and skin or eyes. Additional safety recommendations related to the use of chemical disinfectants are summarized here.

Source: Karin Gallandat

For disinfection to be effective, sufficient contact between the disinfectant and the virus is needed. This means applying the disinfectant so that the surface is completely covered (visibly wet) and leaving the disinfectant - 0.1% chlorine or 70% ethanol - for at least 1 minute before wiping dry.

Diluted chlorine solutions become less effective over time and should be remade daily and stored in a cool, dry place away from direct sunlight.

Porous surfaces

Porous surfaces (such as rugs, curtains, or wood) should be cleaned as regularly as possible with soap and warm or hot water. If possible, this should be followed by generous application of a disinfectant (0.1% chlorine or 70% ethanol) for at least 1 minute. In any case, after cleaning and/or disinfection, items or surfaces should be allowed to dry thoroughly, ideally in sunlight.

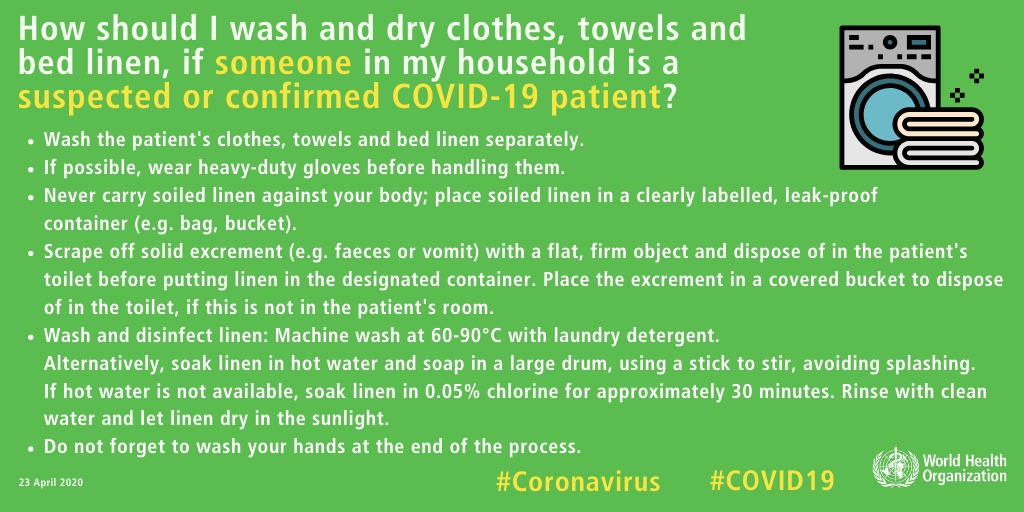

The ECDC recommends that fabrics that are likely to be contaminated (e.g. clothes, towels, or bed linens used by a confirmed or suspected COVID-19 patient) should be stored in a dedicated laundry bag and washed separately. Heavy duty gloves should be used to handle these fabrics if possible and care should be taken not to carry soiled linen against the body. Any soil excrement should be scraped off first with a flat, firm object into the toilet used by the patient, or in a covered bucket which will later be disposed of in the toilet if it is not in the patient’s room. Fabrics should then be machine washed in hot water (60oC-90oC) using laundry detergent or soaked in hot water with soap in a large drum, using a stick to stir. If hot water is not available, fabrics should be soaked in 0.05% chlorine for 30 minutes and then rinsed in clean water. Please note that chlorine may permanently stain some fabrics.

A 0.05% chlorine solution can be prepared by mixing equal volumes of clean water and 0.1% chlorine solution prepared as described above. In any case, with or without disinfection, it is important to ensure thorough drying of laundered items in direct sunlight.

If no one in the household is a suspected or confirmed COVID-19 patient it is not necessary to use a washing machine or drier, or very hot water. Laundry can be carried out in the household’s usual way.

What if disinfection or laundry facilities are limited?

In contexts where limited disinfection and/or laundry options are available, drying objects including kitchen utensils and fabrics in the sun may help kill viruses on surfaces and objects. Most viruses are sensitive to sunlight and heat, including the influenza virus and coronaviruses.

What can we recommend for people living in improvised shelters or houses with dirt floors?

One billion people live in informal settlements. Additionally the UNHCR estimates that 70 million people are currently displaced and living in temporary, improvised or tented housing. Maintaining cleanliness in these settings is a daily challenge, as floors, walls and surfaces often consist of unfinished or natural materials such as wood, mud or plastic and availability of cleaning and disinfection supplies is likely to be limited.

In these settings, it may be impossible to entirely prevent hands getting contaminated by surfaces but handwashing with soap can still interrupt transmission and prevent people becoming infected. We suggest that you recommend the following:

Where possible, look at options for increasing the amount of water and soap available to households so that more regular wet cleaning is possible. Encourage handwashing with soap regularly and remind people to avoid touching their face. Encourage parents to wash the hands of young children frequently. This is important because young children are likely to come into contact with surfaces that are hard to clean (e.g. dirt floors) and then put their hands into their mouth.

Sweeping is a widespread cleaning practice, particularly in places where houses have dirt floors. Sweeping may lead to aerosolization of viruses from the floor: like dust, viruses can move from the floor surface into the air (Study 1, Study 2). The risk of SARS-CoV-2 transmission through aerosols generated by sweeping has not been directly evaluated. As a caution, however, wet cleaning practices should be encouraged whenever possible.

UNICEF recommends that Infection Prevention and Control (IPC) kits be distributed to vulnerable households, including the following key items - to be adapted to local contexts: soap or hand sanitizer, detergent and chlorine-based products, mop and bucket or basin, and, if relevant, a bucket with tap for handwashing. For further information read our resources on distributing hygiene kits for COVID-19 response.

What if someone in my home has been sick?

The cleaning and disinfection processes described above can be followed for all frequently touched surfaces in homes where a suspected or confirmed COVID-19 case occurs. If someone is sick in the household the following additional measures of cleaning and disinfection should be used:

Household items such as eating utensils, dishes, bed linens or towels used by the patient should be cleaned and disinfected separately from other household members’ items following the procedures described under “How should I clean surfaces in my home?”.

If possible, the use of a dedicated bedroom and bathroom by the ill person is recommended. In that case, the cleaning frequency in the spaces used by the ill person should be kept to a minimum (e.g., only clean soiled surfaces), to avoid unnecessary contact with the patient and contaminated surfaces. Alternatively, cleaning and disinfection supplies may be provided to the ill person for them to clean the spaces that they use.

If it is not possible to have dedicated spaces for the ill person, frequent cleaning and disinfection of household surfaces by the ill person (e.g., after each use of the bathroom) is recommended. If the ill person is unable to perform these tasks, the caregiver should use a face mask and gloves (see guidance on use here) to clean and disinfect high-touch and soiled surfaces.

For further guidance about how to shield vulnerable individuals see this article.

Summary of recommendations:

Non-porous surfaces should be regularly cleaned and disinfected where possible with diluted bleach (0.1% chlorine) or 70% ethanol

Porous surfaces should be regularly cleaned, laundered and aired in the sun.

Encourage hand washing with soap as an additional way of interrupting transmission.

How resistant is SARS-CoV-2 to disinfection?

Since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, the resistance of SARS-CoV-2 to various chemical disinfectants has been evaluated. Laboratory studies consistently show that the virus is susceptible to standard disinfectants such as chlorine, ethanol or Virkon (Study 1, Study 2, Study 3) A systematic review of studies using viruses closely related to SARS-CoV-2 also finds that 70% ethanol, 0.1-0.5% chlorine (sodium hypochlorite), and 2.0% glutardialdehyde can inactivate 99.9% of these viruses on stainless steel within 1 minute.

This is consistent with the fact that SARS-CoV-2 was not detected on surfaces in two isolation rooms in Singapore after routine disinfection, which consisted of using 0.5% chlorine (sodium dichlorosisocyanurate, NaDCC) twice daily on high-touch surfaces and 0.1% chlorine once daily on floors. The use of 0.1% chlorine every 4 to 8 hours also kept surfaces and objects free from detectable SARS-CoV-2 in hospital isolation wards in China.

Physical disinfection such as UV radiation can also inactivate SARS-CoV-2 on surfaces: three laboratory studies identified in a systematic review reported at least 99.9% reduction following relatively brief exposures to different sources of UV light.

How can we maintain the cleanliness of public water pump handles?

Public water pump handles can be contaminated by users' hands. We recommend the following measures to keep handles clean:

Installation of a handwashing facility next to the pump so that users wash hands before using the water pump. Read this guide for more information about creating handwashing facilities.

Cleaning and disinfection of the water pump handle as frequently as possible following the procedure explained above for high-touch surfaces in households - i.e. application of 0.1% chlorine or 70% ethanol for 1 minute, ensuring full coverage of the pump handle surface with disinfectant.

Useful resources on surface disinfection

Safe Surface Science is a group of researchers based at or collaborating at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine working on the science and promotion of maintaining the safety of surfaces in homes, healthcare facilities, and other spaces. This webpage provides links to simple videos about safe surface disinfection and a helpful infographic.

Fomite transmission and disinfection strategies for SARS-CoV-2 and related viruses. This review aims to summarize the current knowledge and underlying physicochemical processes of virus transmission, in particular via fomites, and common disinfection approaches. Gaps in knowledge and needs for further research are also identified.

Cleaning, laundry and hygiene tips for households are also provided by UNICEF here.

Waste management in the home

What is domestic solid waste?

Domestic solid waste consists of everyday items such as packaging, disposable cleaning materials or kitchen waste.

The widespread use of disposable personal protective equipment such as masks and gloves combined with the renewed popularity of single-use plastics has led to a dramatic increase in the volumes of domestic waste generated during the COVID-19 pandemic, as highlighted in this report and by the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP).

Domestic waste items, such as cleaning materials or tissues and masks that have been used by an infected individual, may be contaminated with SARS-CoV-2. The virus may survive for hours to days on surfaces, and up to a week on a surgical mask. Domestic waste could thus potentially carry some risk of virus transmission in the absence of adequate waste management systems.

What should be done with domestic solid waste in the COVID-19 context?

According to the European Commission, there is no evidence to date suggesting that domestic solid waste plays a role in COVID-19 transmission and international agencies consistently recommend to follow standard solid waste management procedures.

WHO recommendations for solid waste management in the home in presence of a sick, quarantined or convalescing individual include the following:

Rapidly dispose of potentially infectious materials, such as tissues used when sneezing or coughing or disposable clothes used for cleaning, into a waste bin. ECDC recommends the use of separate waste bins for sick individuals and other household members, whereas according to some national guidelines, all waste produced by households with COVID-19 positive individuals should be considered as infectious waste.

Use strong, completely closed bags to pack waste. Double bagging can also help ensure infectious waste items are safely packed (e.g. a small bin liner could be used by the infected individual, then closed and added to a larger bag for municipal waste collection). To reduce direct contact with potentially contaminated waste, UNEP recommends to seal bags before they are 70% filled. National guidelines should be followed regarding the use of color-coded waste bags or containers.

Waste bags can be picked up and treated by municipal collection services following national guidelines or UN-HABITAT recommendations (and with workers wearing adequate personal protective equipment). In absence of such services, safe burying or controlled burning may be considered as alternatives. Please note that waste with high humidity contents (e.g. food waste) is not suitable for burning, and open dumping or burning of solid waste presents environmental and health hazards. Some recommendations for the safe burying and/or incineration of solid waste are provided here, in this guide (Chapter 5) as well as in this document (pages 18-23).

Wash hands with soap or use an alcohol-based hand rub after any contact with waste.

How should we dispose of used masks and other protective equipment?

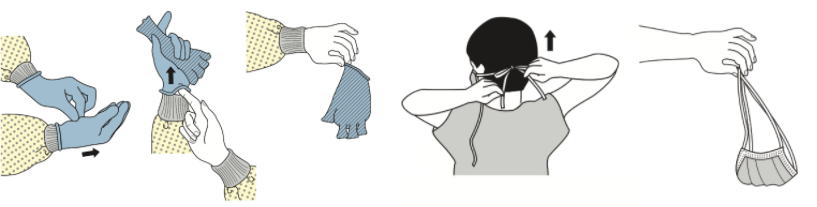

After use, masks and gloves should be removed carefully, avoiding contact with parts of the mask or glove that could be contaminated (e.g. inside of the mask or outside of gloves - see Figure below). Hands should be washed with soap or sanitised using an alcohol-based hand rub afterwards. These videos show in more detail how to properly wear and remove a surgical mask and gloves.

Please note that the use of gloves in community settings is not currently recommended by WHO and CDC, except when caring for a sick individual.

How to remove gloves and masks. Source: CDC

Single-use PPE (such as disposable masks, gloves, or worn-out fabric masks) should be disposed of immediately after their removal, following the recommendations outlined above for domestic solid waste. They should not be recycled or thrown into toilets, where they could clog sewers. Littering of masks and gloves could have dramatic ecological consequences.

Given mask shortages in some settings, the WHO recommends precautions be taken to avoid the collection and re-selling of used masks that have been disposed of. Besides completely closing waste bags, these precautions may include defining fenced, regulated areas for waste disposal. Context-specific risk communication and community engagement strategies should also be considered to protect informal waste pickers if relevant.

Promoting reusable fabric face masks can minimise unnecessary waste. Reusable (fabric) masks should be washed and dried according to manufacturers’ instructions - general guidance is provided in this section.

What other resources are there on solid waste management?

The International Solid Waste Association (ISWA) documents solid waste management practices and guidelines across different countries on their website.

Editor's Note

Author: Karin Gallandat

Review: Karen Levy, Jacqueline Knee, Sian White, Robert Dreibelbis, Molly Patrick, Sheillah Simiyu, Alessandra Ginocchi

Last Update: 29.07.2021